Lies proliferate on social media, and it is even harder to sift out truth from fiction when it looks like the message is coming from a real person. Mix in some uncertainty as to whether the falsehood is part of a deliberate campaign to hurt the company or just typical online shenanigans, and it's the beginnings of a security headache.

Dealing with false claims posted on social media or other online platforms falls under online reputation management and is generally the responsibility of marketing or public relations, not traditional security. And while disinformation is getting a lot of attention in security circles, the discussion primarily tends to be in the context of election security. However, hacking social media accounts, or creating fake accounts, to post false messages about a company is absolutely a disinformation campaign and warrants at least some kind of a discussion within the security team.

“We are seeing more instances of individuals and groups using disinformation tactics to target companies, which is much more than a brand issue,” said Cindy Otis, director of analysis at Nisos.

Earlier this week, a Twitter account belonging to an English professor posted that Olive Garden was one of the companies “funding Trump’s election in 2020” and suggested that people should stop going to the restaurant. As is fast becoming common whenever politics and well-known brands collide, Twitter users responded with calls for a boycott. Over a two-day period, the #BoycottOliveGarden received more than 52,500 mentions (including tweets, quote tweets, and retweets) by 48,700 users, and had a reach of 139.4 million and 169.4 million impressions.

The initial message was false.

“We don’t know where this information came from, but it is incorrect. Our company does not donate to presidential candidates,” the restaurant chain posted on its social media channels over and over again, trying to counter the boycott messages. When the speculation switched to the restaurant’s parent company, Olive Garden added, “To clarify, Darden does not donate to federal candidates.”

While this looked like just another day of social media monitoring and political discord on Twitter, there was a twist: the person was not responsible for the initial message.

A Cascade

About a day after the initial message was original posted, the owner of the account said someone had compromised the Twitter account and posted that false detail about Olive Garden. The original message was removed and the account owner tried to set the record straight, but lies spread much more readily on social media than truth. And once a lie gains traction, it is really hard to debunk it.

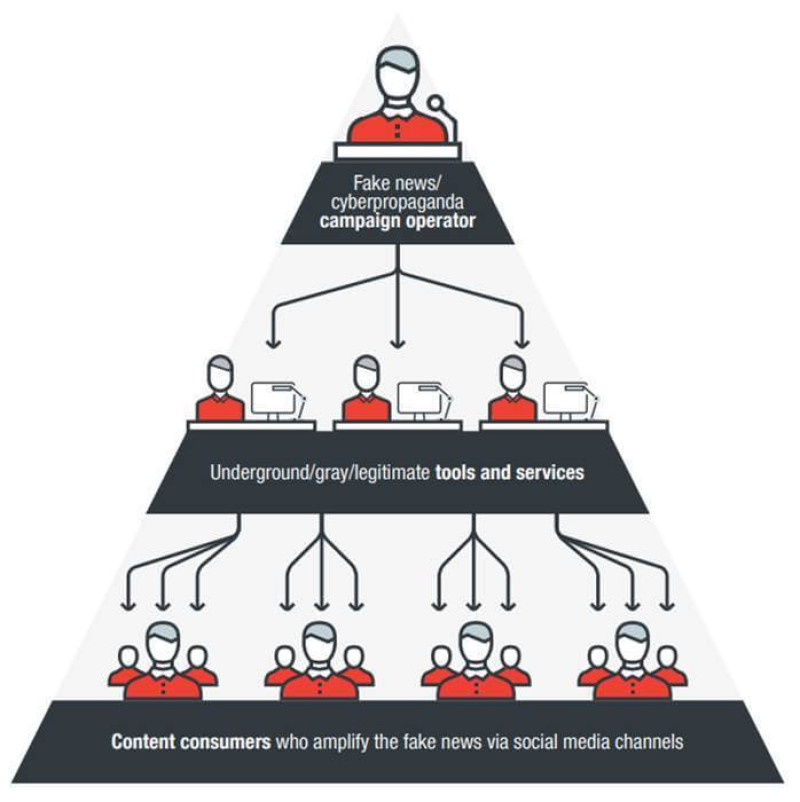

“Social media posts like this were often the initial stages of a cascade,” said Greg Young, vice-president of cybersecurity at Trend Micro. The more legitimate an account appears, the more likely that the message will get amplified. A compromised account—such as that of an established English professor—is the “perfect seed,” Young said.

While disinformation campaigns frequently rely on a bot army or a network of fake accounts to post and spread the false content, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology research found that false reports get retweeted more by humans than bots. This is the cascade Young mentioned—as the false information percolates through the platform, the legitimate uncompromised accounts increase the campaign momentum as regular people start pushing the content.

“The idea was to get the ball rolling in order for the natural effects of a social network to take the planted message and make it trend,” Young said.

Misinfo-as-a-service

Abusing social media to damage an organization’s reputation is commonly used tactic, and according to Trend Micro’s research on Twitter activity, spreading misinformation is a common service offered in underground and “gray” marketplaces. Researchers identified examples of services offering to post messages by "influential" accounts with thousands of followers and other types of manipulation campaigns in an earlier Trend Micro report on disinformation online.

These offerings can be considered an “outgrowth of existing services such as black hat search engine optimization, click fraud, and the sale of human and bot traffic, Trend Micro wrote at the time.

In this instance, one false tweet was able to reach more than 100 million people. “A coordinated plan to hack multiple accounts to spread disinformation could have more devastating consequences,” Otis said.

Breach Lesson

The Olive Garden incident highlights another important lesson about post-data breach response. The email address associated with the Twitter account responsible for the initial post about the restaurant and the password for that email account were both exposed in an earlier (different) data breach, Otis said. As the information was available in underground forums, there are two possible ways the Twitter account was compromised: the attacker tried the email password and found that the password had been reused, or the attacker had control of the email account (using the exposed credentials) and reset the password using Twitter’s forgot-password mechanism.

It’s not known whether the same password was reused for Twitter, but password reuse continues to be a problem. The original poster admitted having been advised, repeatedly, to change passwords after the email account was compromised, but had not done so. With the recent wave of data breaches, the reminders to change passwords can get annoying, but it is an important first line of defense to keep accounts from getting compromised. Turning on multi-factor authentication boosts the odds even more.

Typically, when victims are told to change their passwords, and to make sure they aren't reusing passwords, the focus is on follow-up attacks against them. Lose control of the email account and bank accounts will be compromised. Personal information leaked means potential for spear phishing attacks. But as this incident shows, the attacker may not care about the owner of the account at all. The account is a way to get ahold of the tools necessary to carry out an attack completely unrelated to the breached victim. In this case, a social media account that can be used to mess with a chain restaurant.

Might be a Coincidence

Earlier in the month, a handful of Twitter accounts circulated a list of popular fast-food restaurants supposedly supporting the re-election campaign. The list didn't get a lot of attention initially, and the Washington Post said the information was incorrect, but the list continued to float around. The fact that Olive Garden was included on that list may just be a coincidence, or it may indicate some kind of an advance effort was underway to lay the groundwork for this kind of a campaign.

It's a cycle. Someone may see a post on social media about a company. If a quick search (usually on the same platform) pulls up other people talking about the same post, as well as older posts that seem to be talking about the same thing, then it gives credibility to what is on the post.

Social media monitoring is a valuable intelligence gathering tool, as security teams can uncover details about ongoing threats and attack indicators buried inside social media posts. Social media posts are often the first indicator when issues are being exploited or a company is being targeted. This also means expanding the definition of disinformation to consider that things posted online can directly impact a company's overall risk, as well.

The cascade: An operator at the top spreads a false piece of information by employing a network of fraudulent and compromised accounts, and then waits for regular people to amplify the message. Source: Trend Micro.