CANCUN--The mobile app world represents something of a conundrum for attackers. On one hand, it’s a massive opportunity for profit, with billions of devices available and just as many users willing to install random apps. But on the other hand, Google and Apple, the owners of the dominant app platforms, have made it increasingly difficult to get malicious apps into their stores and onto victims’ devices.

The strict rules and developer security requirements that both companies have put in place have kicked off a long-running game of one-upmanship between the platform providers and malicious app developers. That back and forth has involved a lot of moves and countermoves in the last couple of years, as both Google and Apple have been forced to counter new tactics from the criminals. One of the new fronts that has opened up in this conflict involves efforts from app developers to defeat Google’s reverse engineering efforts that inspect apps in the Play store.

Google uses its inspection system to check the functionality of apps, ensure that they don’t have any undocumented features or monitor users without proper notification, among other things. Legitimate apps that do monitor devices have to go to great lengths to make sure users are aware of their features and how the information is being used. But malicious app developers always are looking for ways to circumvent this barrier, and their tactics are becoming more and more creative all the time.

“Monitoring apps have to comply with a long list of rules and provide constant notifications to users. And they can’t force users to download anything from outside of the Play store,” Łukasz Siewierski, a member of Google’s Play security team, said during a talk on anti-reverse engineering tricks at the Kaspersky SAS conference here Friday.

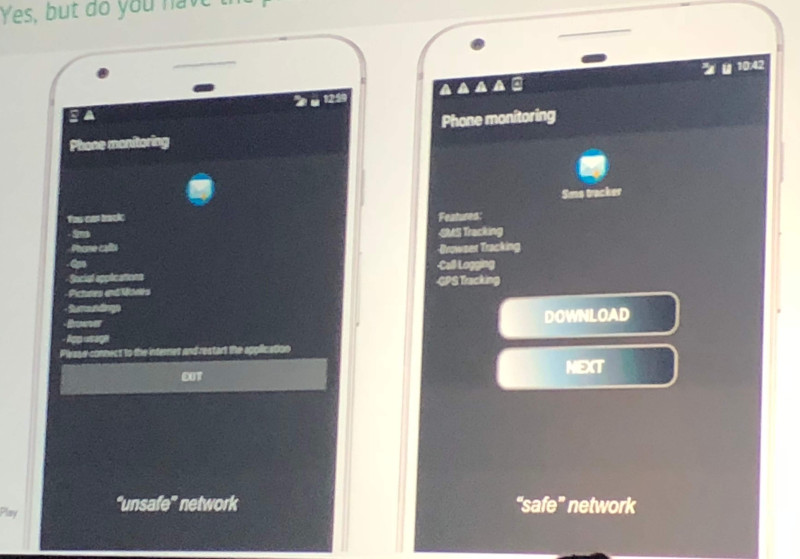

Siewierski called out an example of one app that checks to see if it’s on a Google network when it starts. If it is, it will send a different response from the command control server than if it’s on an outside network. Running the app on a Google network will show a screen that describes all of the functionality and what the app can monitor. A user on a non-Google network will see a screen that shows a small subset of the monitoring features and asks her to download another app from a third-party source, which then does all kinds of hidden monitoring.

“The first app is just a shell,” Siewierski said.

A second app Siewierski described goes even further, not only checking for a Google network, but also running a check to see if it’s on a Google Android device, such as a Pixel or Nexus. If either of those answers is yes, the app simply gives the user a screen asking for a username and password ro register, but then does nothing; it has no actual functionality. But on non-Google networks and devices, the app will try to get the user to download a second app that then hides itself completely on the device, with no icon or other visible indication of its presence.

“It can then bootstrap the device in a covert way,” Siewierski said.

All of these machinations are an indicator of how far malicious app developers have to go to get around the protections that Google has put in place to prevent malicious apps from getting onto users’ devices. Raising the cost of doing business for attackers is a big part of the security strategy for both Google and Apple and they’re succeeding to a large degree. But as they enhance their protections, the app developers continue to adapt, as well.

Some malicious apps will present different screens depending on the network on which they're running.