Attackers launched a massive distributed denial-of-service against a specific website hosted by a hosting provider in early June. Not only was the 1.44 terabit-per-second DDoS attack the largest Akamai has seen to date, it was also one of the most complex to resolve, according to Akamai.

“The attack appears to have been a planned and orchestrated effort–and appears that someone was very intent on maximizing damage,” Akamai said.

This attack had a bandwidth of 1.44 terabits-per-second and 385 million packets per second and lasted about an hour and a half, said Roger Barranco, vice president of global security operations for Akamai. The attack sustained 1.2 terabits-per-second for an hour.

The hosting provider, which Barranco declined to name, hosted a number of political and social sites. The provider itself was not the target, as the attack seemed to be making a statement about the site. Barranco also said there wasn’t a way to definitely draw a link between current events and the site that was under attack.

There were other smaller attacks against the provider during this time period, such as the 500 gigabit-per-second DDoS attack against a different website. But being able to sustain high traffic volumes for that long a period of time is unusual in a DDoS attack when most attacks are measured in minutes.

A Well-Coordinated Attack

A typical DDoS attack depends on one to three different attack vectors, but this one utilized nine, Barranco said. The methods involved volumetric attacks, or floods, of ACK, SYN, UDP, NTP, TCP reset, and SSDP packets, multiple botnet attack tools, and CLDAP reflection, TCP anomaly, and UDP fragments. There were no zero-day vulnerabilities and novel techniques, Barranco said.

The variety is unusual because of the sheer amount of planning and coordination that would have been required. While attack infrastructure can be rented, there is a limited reserve of tools that can be used, and other attackers putting together their own campaigns are competing to use those tools, as well.

“Someone went way out of their way to reserve the capability and collect the tools needed for an attack of this size,” Barranco said.

Geographic concentration tends to be typical for DDoS attacks, so the fact that the attack was made of globally distributed traffic was notable. There have been geographically-dispersed attacks in the past —the Mirai botnet had “some continental and geographic distribution, but not to this extent,” Barranco said—but this attack used the regions differently. There was a primary attack vector associated with the regions, so the traffic coming from the United States used one method, and traffic from another region used a different type of attack.

The most prominent sources of traffic were San Jose and Frankfurt, Germany.

Barranco didn't know if this was just one very skilled and knowledgeable individual or a group working very closely together, but said it was not very likely that multiple groups were working together.

Growing in Size

There are many denial-of-service attacks in a typical year, many of them against gaming sites, but most of them tend to be small and short-lived.

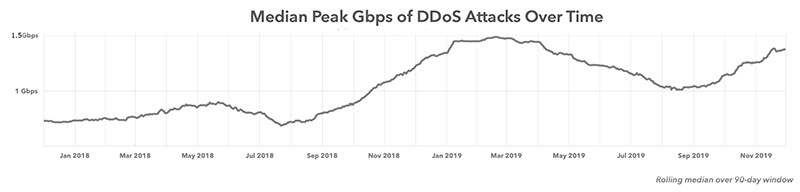

Attacks usually double in size every two years, Barranco said. At the end of last year, DDoS attacks were typically small and short in duration, although the sizes had been increasing slowly. Barranco noted the median bandwidth size for attacks doubled from about 300 gigabit-per-second to 600 gigabit-per-second two years ago. In that sense, the June incident appears to be right on schedule.

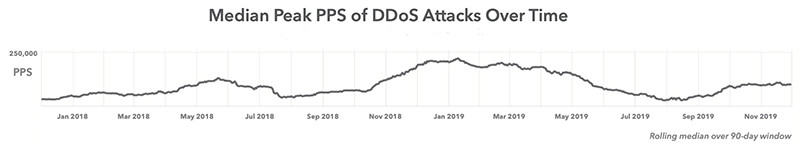

It’s easy to focus on just the gigabit per second (or in this case, terabit-per-second) because they are large numbers, but packets-per-second is an important metric to pay attention to, as well. An attack with relatively low packets-per-second can still take down a business because the network equipment can't handle the amount of traffic being sent even though the network capacity is not saturated. A DDoS attack against an online bank and credit card issuer in April 2019, at 39 gigabit-per-second and 113 million packets-per-second, was the largest attack by packets-per-second that Akamai had seen up to that point, according to Akamai's latest State of the Internet report.

"While the packet count for this attack was extremely high, individual packets were relatively small, limiting the volume of traffic created," Akamai said.

Large providers frequently have to deal with large attacks. Amazon Web Services was hit with a 2.3 terabit-per-second DDoS attack earlier this year, as attackers unsuccessfully attempted for three days to knock services offline, according to Amazon’s Q1 AWS Shield Threat Landscape Report. The hosting provider was hit with smaller traffic volume than Amazon, but Barranco noted the difference in packets-per-second between the two attacks. AWS was hit with 293 million packets-per-second, making the June attack on the hosting provider, with 385 million packets-per-second, “quite a bit larger,” Barranco said.

That doesn’t mean that the AWS attack was less serious—dealing with large volumes of attack traffic (in this case, CLDAP reflection) for over three days is never a picnic.

Knowing Good Traffic From Bad

Akamai’s Security Operations Command Center handled the bulk of the attack in seconds, but it still took about ten minutes to get it under control, Barranco said. The hosting provider noticed the impact of the attack only for a few minutes.

Enterprises need to really understand their ingress traffic so that they can respond to a DDoS attack effectively, Barranco said. Otherwise, they may wind up crippling their own network while trying to stop the attack. DNS traffic, for example, may make up about 1 percent of the enterprises’s total traffic, but it is the most critical. If an enterprise responded to a DNS flood or a DNS amplification attack by blocking DNS traffic, the entire enterprise’s business operations could come to a standstill because the enterprises didn’t realize the how much the enterprise depended on that small volume of legitimate packets. Similarly, if the attack used NTP floods, blocking NTP could prevent corporate machines from operating normally. A defender may not know which packets to keep if the attacker employs multiple types of traffic,

The challenge is to “stop the [attack] traffic while still letting the good traffic in,” Barranco said.

Over the past 24 months, the attacks were fairly small, although they were steadily growing in size. The pace is slow and steady over the time period, but the attack size typically doubles around the two-year mark. Call it Barranco's Law of DDoS Attacks, if you will. The charts show the median bandwidth peaks and packets-per-size for the last 24 months. [Source: Akamai's State of the Internet report (Volume 6, Issue 1)]