NEW YORK—Time time for dilly-dallying and shilly-shallying is over. United States Attorney General William Barr wants technology companies to create methods and backdoors that will give law enforcement access to encrypted communications and data. First order of business: make it possible to read messages sent via encrypted messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Apple’s Message.

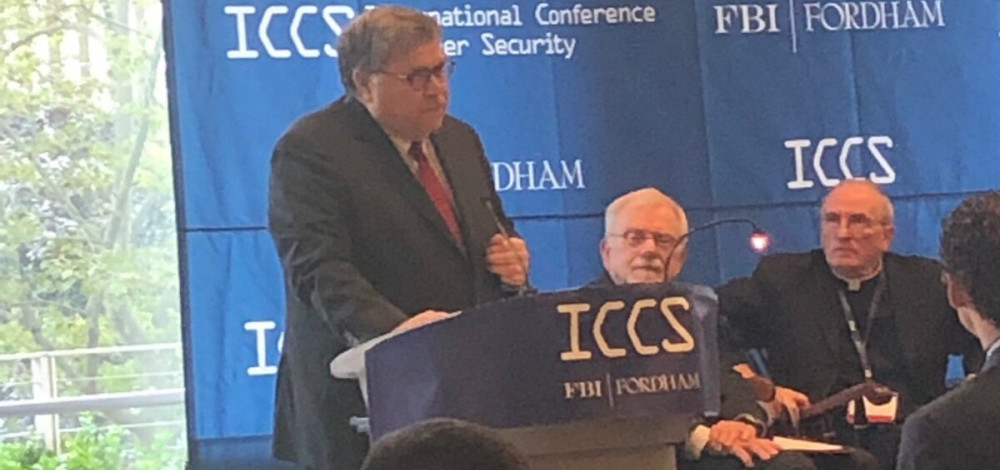

“Encryption provides enormous benefits to society by enabling secure communications, data storage and on-line transactions. Because of advances in encryption, we can now better protect our personal information; more securely engage in e-commerce and internet communications; obtain secure software updates; and limit access to sensitive computers, devices, and networks,” Barr said in a speech at New York City’s Fordham University. But encryption isn’t so wonderful, because it also means criminals can talk to each other and plan their activities without law enforcement being able to listen in.

“With the growing availability of commoditized encryption, it is becoming easier for common criminals to communicate beyond the reach of traditional surveillance,” Barr said.

This isn’t a new point—various law enforcement officials, intelligence heads, and lawmakers have argued for nearly two decades that more communications and data being encrypted means less visibility in what the bad guys are doing. The request for backdoors that only law enforcement can use (authorized with a warrant) or workarounds involving special keys that can also decrypt contents have been made before repeatedly. Security experts—namely the cryptographers who understand how encryption works—have criticized these proposals implementing them would weaken encryption and allow malicious actors to take advantage of the feature. Even though the U.S. attorney general didn’t break new ground with statistics, cases, or new arguments, his speech signalled a subtle shift in the government’s stance in this so-called debate.

Past demands have focused broadly on law enforcement needing access to data—names and information about contacts, images or other files, as well as actual messages—and Barr echoed that talking point, initially. "Law-enforcement agencies are increasingly prevented from accessing communications in transit or data stored on cellphones or computers, even with a warrant," Barr said.

However, Barr pivoted from data and specifically called out encryption messaging apps for making it difficult for law enforcement to do their jobs. Criminal organizations are increasingly relying on encrypted messaging apps to plan and coordinate their criminal enterprises, Barr said, citing a “large violent gang” who use these apps to “green light” assassinations and “human traffickers and pedophiles” who use the apps to “facilitate” their activities. One of the shooters in the Garland, Texas shooting back in 2015 allegedly exchanged messages with “an overseas terrorist” using an end-to-end encrypted app, and federal agents still have not been able to “determine the content of these messages.” A “Mexican cartel” is using WhatsApp as their “primary communication method” to ship finished fentanyl from Asia to Mexico to the U.S. and make plans to kill specific Mexico-based police officers.

“Had we been able to gain lawful access to the chat on a timely basis, we could have saved these lives,” Barr said.

The use of encrypted messaging apps is increasing, and tech companies are beginning to build in end-to-end encryption into existing products. Barr’s argument is that if more people are going to use those apps, then they can’t be “warrant-proof.”

“What’s really fascinating about this speech is how frankly the...administration has moved away from ‘we just want to access your encrypted phone’ to making it clear that communications (text messages) etc. are the real goal,” Matthew Green, cryptographer and professor at Johns Hopkins University, wrote on Twitter.

Encryption Isn’t Binary

Barr acknowledged the benefits of increased use of encryption, noting that “we can now better protect our personal information; more securely engage in e-commerce and internet communications; obtain secure software updates; and limit access to sensitive computers, devices, and networks.” However, he framed the current status quo as a binary choice, protecting people in the online, digital, world meant living in a less safe physical world. Thanks to encryption, he implied, the real world was more dangerous because the virtual—not real—world was secure.

He goes even further, casting the choice as between “hackers” and “violent criminals, terrorists, drug traffickers, human traffickers, fraudsters, and sexual predators.” Hackers don’t cause as much damage or pain as much as these real criminals do, and crimes committed in the digital world aren’t as serious as the ones that happen in the physical world.

“[Making] our virtual world more secure should not come at the expense of making us more vulnerable in the real world,” Barr said.

And even in the digital world, Barr seemed to suggest that some things needed more protecting than others. "We are not talking about protecting the nation's nuclear launch codes" or the encryption formats used by large businesses, but rather "consumer products and services such as messaging, smartphones, email, and voice and data applications," Barr said. If there is a hiearchy of what deserves to get protected, what regular people say or do online appear to be way at the bottom of the heap.

That is a disturbing line of reasoning from the nation’s top prosecutor.

“Making our virtual world more secure should not come at the expense of making us more vulnerable in the real world.”

As Green noted, the federal government isn't using a different encryption protocol than what is being used in commercial products. They are buying commercial products from the same vendors businesses rely on. So, it is quite likely the same encryption is actually being used to protect the launch codes. Saying messaging apps should use a different encryption mechanism that is strong enough to keep out attackers but still let law enforcement ignores the fact that strong enough means relying on the same cryptographic principles.

Attackers aren't just going after the arsenal and the vaults. They are looking to get in using commercial software and tools.

"It is generally agreed that events like the Office of Personnel Management breach were a catastrophic blow to our intelligence agencies," Green said.

The continued insistence that encryption backdoors ignores the fact at least one adversary group had already found and abused one such backdoor at some point. Back in 2015, Juniper made a surprising announcement that it had found unauthorized code in some NetScreen firewalls. After an investigation, it turned out the Dual EC backdoor could give attackers full control of the appliance and the ability to decrypt all traffic flowing through.

The ultimate targets and details of the Juniper attack are still not public," Green said. "There is a good chance that this continued secrecy hides one of the more catastrophic breaches in US history.

Get It Done, He Says

Cryptography experts have repeatedly said there isn’t a way to implement a workaround or special mechanism for lawful access to encrypted messages, but officials like Barr continue to insist that if could be done, if only the experts would put their heads together and get to work.

There have been enough dogmatic pronouncements that lawful access simply cannot be done," Barr said. "It can be, and it must be.

“Some who resist lawful access complain it places an unreasonable burden on companies, who must spend time and resources on developing and implementing a compliance mechanism. To that, I first say, ‘Welcome to civil society,’” Barr said. “’If my business plan is to sell sawed-off shotguns,’ That’s tough. We as a community have a right to say, ‘No, we don’t care if that’s your business plan, the barrel has to be this long.’”

Barr referenced the fact that some products rely on centrally managed keys to access software update portals, and said the Department of Justice knew “of no instance where encryption has been defeated by compromise of those provider-maintained keys.” Actually, there have been at least one such case. Stuxnet was one. NotPetya spread by compromising a software update mechanism, and a group of attackers subverted the software update used by ASUS to push out malware on to user computers.

“We think our tech sector has the ingenuity to develop effective ways to provide secure encryption while also providing secure legal access,” Barr said. There were three earlier proposals—the United Kingdom’s GCHQ, Ray Ozzie’s hardware concept, and Matt Tait’s Layered Cryptographic Envelopes—but they need to be refined and alternatives considered.

"We do not seek to prescribe any particular solution," Barr said. "Providers are in the best position to determine which methods work best.” While, they shouldn’t take too long to come up with ideas because the longer it takes to come up with a new approach, the “ability to protect the public” is being diminished, Barr said.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore) accused Barr of wanting to “blow a hole” in encryption by advocating for backdoors. “Encryption is one of the few security techniques that mostly works,” Wyden said on Twitter. “We can’t afford to mess it up.” “[B]anning encryption in America will not stop bad guys from using encryption. It will not ban basic math and algorithms elsewhere in the world. It will only leave Americans less secure against foreign hackers, Wyden said. "Once you weaken encryption with a backdoor, you make it far easier for criminals."

"It's only a matter of time before a sensational case crystallizes this issue in the public eye," he said. That sounds like a threat.