Internet security is based on a delicate ecosystem of trust between certificate authorities, browsers, and users. Some CAs are making potentially misleading and confusing claims about the digital certificates used to protect online communications and websites, prompting several security experts to call them out.

The CA Security Council, an alliance of certificate authorities formed in 2013 to collaborate on security and best practices for digital certificates, recently announced its London Protocol initiative at a CA/Browser forum event. The council hopes to address the growing problem of criminals obtaining legitimate certificates to use on phishing sites through its four-phase ten-month initiative.

CAs are blaming the influx of domain-validated certificates for the phishing problem.

Comodo CA, Entrust Datacard, Globalsign, GoDaddy, and Trustwave pledged to work together on policies and procedures to “improve website identity assurance” and present a report with recommendations on how other CAs can adopt and implement the new protocols.

This sounds like a laudable project, since phishing is one of the biggest online threats facing organizations and individuals. The problem with the London Protocol is that the participating CAs are blaming the influx of domain-validated certificates for the phishing problem.

Primer on Certificates

Transport Layer Security (an updated, more secure, version of the Secure Sockets Layer protocol) encrypts data sent between the site and the user’s machine so that eavesdroppers can’t see or modify the contents of the network traffic. There are two uses for TLS for websites: to protect traffic in transit to and from the site, and to assure users that the site they are visiting passed the identity checks and is owned by the entity it is claiming to be.

There are three main types of certificates used for TLS: Organization Validated (OV), Extended Validation (EV), and Domain Validation (DV). The idea is that the domain owner provided a business license or another form of identification, or passed an identity verification test in order to get the EV certificate. OV certificates have a lower burden of proof. The CA has verified that the owner of the website is really who it claims to be—the domain owner claiming to be Google really is Google. When the CA issues a DV certificate, it has checked the entity requesting the certificate actually owns the domain. The DV certificate is used to protect the traffic going to and from the domain so that someone can’t hijack network traffic intended for someone else.

EV proves identity. DV indicates ownership. Different purposes, different use cases. Both important. Both secure.

Free and low-cost SSL/TLS certificates have been around for years, but they have gained prominence in recent years as Let’s Encrypt, a free certificate authority from the Internet Security Research Group hosted by the Linux Foundation, has gained steam in its goal to make encryption the default for the web. Let’s Encrypt makes it easier for website owners to obtain, manage, and renew DV certificates (protect traffic) and has issued over 315 million certificates since its inception in 2015. The side effect is that it is also easier for criminals to get certificates for their malicious sites. Last year, The SSL Store, a division of security company Rapid Web Services, warned that Let's Encrypt had issued 15,270 certificates to domain names that have ‘PayPal’ in the name, and that well over 95 percent of those sites were malicious.

DV Not the Issue

Organizations want to ensure users are going to websites where their information is properly protected, and that users are going to sites that aren’t pretending to be something else. That's understandable. Goals conflict when browsers mark websites with DV certificates as “Secure” to indicate the connection is encrypted and users translate “Secure” to mean safe. Users are not very good at recognizing that a site marked “Secure” can still be malicious, but CAs hawking EV certificates as the better alternative to DV is not the answer.

Some CAs have been pushing the narrative that DV certificates are more prone to phishing attacks than EV certificates because criminal enterprises can’t pass the identity-verification process while masquerading as well-known brands. Theoretically that is true, but that assumes the CA in question has stringent rules for vetting identity and is adhering to the CA Browser Forum Baseline requirements for certificate assurance. That’s a big “if.”

“This claim is made without any recognition or acknowledgement that their identity-vetting methods and processes are completely unreliable as practiced. It's a bit like hawking ‘certified-organic’ on your snake oil, and hoping no one will look into what it actually is,” Ryan Sleevi, a software engineer working on the Google Chrome team, wrote on Twitter. In the same thread, Sleevi pointed out the methodology flaws in CA-supported research claiming EV certificates prevent phishing, such as a “flawed and arbitrary dataset,” ambiguous definitions of “safer,” and cherry-picking which certificates to analyze.

The recent primary focus on phishing does not fulfill the purpose for which CASC was created.

CAs have arbitrarily revoked EV certificates for websites without clear explanation in the past, which contradicts the implication that EV certificates can’t be found on fraudulent sites.

Unfortunately, it looks like the London Protocol is continuing this line of argument with its emphasis on identity assurance for websites. Participating CAs will focus on ways to “reinforce the distinction between Identity Websites and websites encrypted by domain validated (DV) certificates, which lack organization identity,” the CA Security Council wrote in its statement.

“[The] FUD from the CA Security Council is deafening,” security expert Troy Hunt wrote on Twitter. While he was specifically referring to a marketing video from the council, the comments were part of his response to CAs touting the benefits of EV certificates in the wake of the London Protocol announcement.

Wrong direction

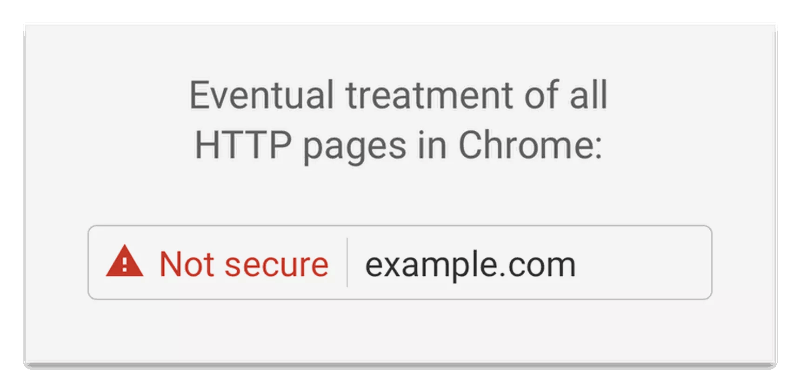

By trying to distinguish between EV and DV certificates, the CA Security Council is going in the opposite direction of the browsers. Users automatically assume that HTTPS and the presence of the padlock icon means the site is good even if the website address looks a little dodgy, because major browsers currently display the name of the organization and the word “Secure” (EV certificates) or just the word “Secure” (DV certificates) in the URL bar. Google is currently testing removing those cues in Google Chrome and relying on new (and simpler) indicators marking HTTP sites as “Not Secure.” Currently, Chrome is the only browser testing this change, but in many things related to website security, where Google leads, other browsers follow.

If certificates were really the problem, the world’s most-phished websites, which include Facebook, eBay, Amazon, Netflix, and Pornhub, would not be betting their multi-million dollar businesses on DV certificates. “If you buy an EV cert for your site, that doesn't stop a phishing site getting a DV cert which people trust just as much because 99.x% of people have no idea what an EV cert is anyway!” Hunt wrote, accusing the CA Security Council of caving into marketing pressure from from member CAs.

We need to assume the Internet is secure by default and using HTTPS.

DigiCert, the certificate authority which purchased Symantec’s website security business last year, recently withdrew from the CA Security Council over disagreements over the council’s fixation with phishing and EV certificates.

“DigiCert is electing to withdraw from the CA Security Council (CASC) as we believe CASC is moving in a direction that DigiCert does not support,” Jeremy Rowley, vice-president of business development and legal at DigiCert, said in a statement. DigiCert “strongly believes in the value of identity provided by CAs” but also believes "EV certificates can be significantly strengthened without negatively impacting the ability of legitimate businesses to get EV certificates,” Rowley said.

"The recent primary focus on phishing does not fulfill the purpose for which CASC was created. We would have preferred if the focus of CASC had instead broadened to address the many challenges and opportunities that the CA industry faces,” Rowley said. DigiCert senior director Dean Coclin said DigiCert will continue working with various industry standards groups and consortiums such as IETF and ICANN to improve PKI and strengthen TLS certificate standards for the web and in IoT.

In a separate statement, Rowley said the London Protocol originally envisioned CAs consuming high-quality threat intelligence information from multiple sources, but that plan was abandoned in favor of building out a common database which participating CAs will query to find related phishing reports before issuing EV or OV certificates.

“The goals of the London Protocol are much less ambitious, with ad hoc data being shared among participants strictly focused on the problem of phishing,” Rowley said. “We would prefer that if CAs are going to engage in website monitoring and information sharing, that it would address the full spectrum of fraud and abuse that exists.”

EV proves identity. DV indicates ownership. Both important. Both secure.

Security experts are on the side of more sites using HTTPS, whether that is EV, DV, or OV certificates, and not perpetuating the myth that only sites collecting data need to be on HTTPS.

“I'm not against EV, I'm against the misrepresentation of what it achieves,” Hunt said."By all means, go and get an EV cert, but don't expect it to make an ounce of difference to your customers getting phished.”

We need to assume the Internet is secure by default and using HTTPS, and to call out sites still on HTTP. The assumption isn’t far-fetched, since Mozilla’s latest telemetry results show that that 70 percent of websites loaded by the Firefox browser used HTTPS.

The CA should not be trying to handle both privacy and identity. “I don’t think that should be the CA’s responsibility, we already have both browser vendors and ISPs doing this,” Hunt wrote.