Late last year, Duo Labs decided to look at the Windows-based Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) laptops that the average person buys from their local big box electronics stores. While there are many organizations that review these devices from a usability and performance aspect, no one has ever really focused on the security of the devices. This was our attempt at filling this gap.

We purchased a total of ten Windows OEM laptops. We based the selection on what was listed on big box electronic stores as the “most popular” and tried to get samples from more than one location. We acquired the following:

- Lenovo Flex 3

- HP Envy

- HP Stream x360 (Microsoft Signature Edition)

- HP Stream (UK version)

- Lenovo G50-80 (UK version)

- Acer Aspire F15 (UK version)

- Dell Inspiron 14 (Canada version)

- Dell Inspiron 15-5548 (Microsoft Signature Edition)

- Asus TP200S

- Asus TP200S (Microsoft Signature Edition)

We felt this would give us a nice mix of popular vendors, a little variety with non-US versions, and the inclusion of Microsoft Signature Edition models with their Microsoft-advertised, non-bloatware versions providing more of a “base” install.

Our Findings

Fail. We don’t want to be harsh, but in general, the results were just “fail” and we really don’t have a better one-word result.

We found the first issue within a few short hours of opening the boxes. That became known as the eDellRoot issue, and while we intended to handle and document our disclosure process, the Internet also found it later the same week, so we tipped our hand.

- A network traffic analysis uncovered numerous security implications with various protocols on all laptops.

- Multiple privacy issues were discovered on all laptops.

- OEM vendor software (the added bloatware) existed on all laptops. And while they contained less bloatware, this did include all three of the Microsoft Signature Edition laptops.

- A cursory examination of the bloatware made our security researcher eyes widen, but in the interest of time, we decided to focus on looking at OEM software that used automated calls to the vendor for bloatware updates, and issues were found with all vendors.

Methodology

To start, we set up a Wireless Access Point (WAP) to connect our laptops to in order to ensure we could capture all traffic. Each person on our Labs team grabbed a laptop off the stack and started configuring it. The initial batch was seven laptops (later three more were purchased).

We took them apart, pulled the drives and made copies, made snide comments about which ones seemed physically weak (only the Lenovo seemed like a solid piece of hardware, many earned nicknames like “blue plastic piece of s#!&”), and quickly realized this was going to take forever.

It became apparent that a lot of the “under the covers” network access when one used a live.com account was insane with all kinds of extra traffic, and it wasn’t required that you sign up for a live.com account, so we didn’t. Even leaving out all traffic associated with live.com, there was plenty to look at. So we made the live.com aspect “out of scope,” even though there were some rather interesting things going on, particularly in the form of bursty traffic MSMQ data. For some details on some of the network traffic we observed, check out Bring Your Own Dilemma OEM Laptops and Windows 10 Issues.

Looking for areas to explore to get a handle on how to scope these things just yielded more bugs. We looked at OEM certificates, which led us to find and research the eDellRoot issue immediately, only to have others on the Internet uncover the same thing a few days later. We paused other research to work on getting our eDellRoot research published to ensure that the most accurate information was available online, and to clear up any questions we saw on social media.

One can assume that various pieces of OEM bloatware are acquired from different sources - corporate acquisitions, in-house development efforts, various licensing agreements, maybe even “pay us and we will include a trial version of your software” deals. You get the idea. And one can also assume that the coding practices are extremely varied and subject to any number of potential security issues. What a rich playing field for researchers! Too rich, really.

We looked at just one class of OEM software - updater programs that must automatically talk to OEM vendor home servers and grab new versions of various pieces of bloatware. We focused on these since we figured this was where some of those OEM certificates might come into play, and since we’d looked at certs, this seemed like a logical next step. That become its own mess, so we simply left it at that, just to get to this point.

Sure, the amount of OEM bloatware on these laptops is rather staggering, so by comparison it should have seemed like the Microsoft Signature Models would be more secure. Of course, you guessed it, they weren’t. After all, they were still running Windows with all of the issues we were seeing on the sniffer, and they still had some bloatware.

General Results

Categories

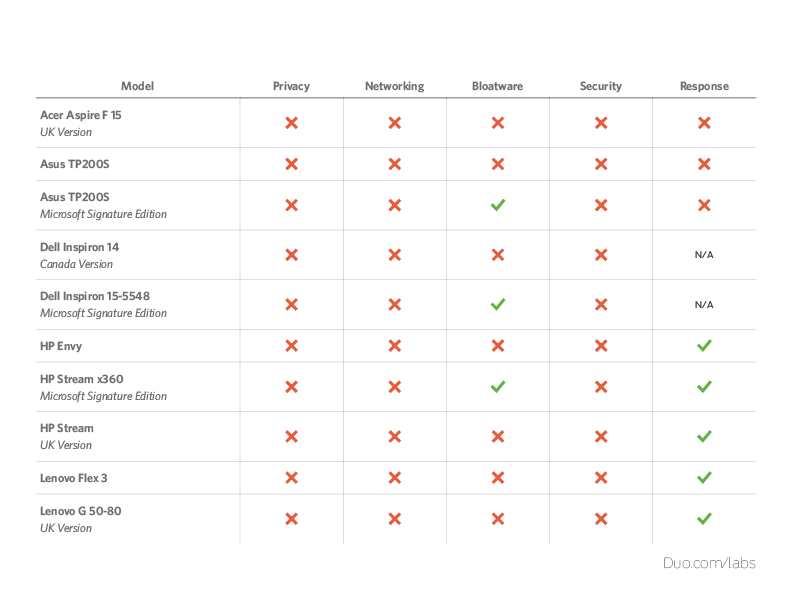

Privacy

We analyzed the OEM systems to determine if they were acting in a way that was not in the best interest of the user's privacy. This includes handling of personal data, third-party system telemetry, non-intuitive methods of disabling privacy features, and anything else that might overly expose users.

Networking

We analyzed the network traffic from the moment they connected to a network after being unboxed and powered on until they reached the desktop. We looked for unsafe use of protocols, firewall settings, and catalogued/analyzed the various connections to servers done without direct user permission.

Bloatware

We analyzed the amount of third-party software, also known as bloatware, that was installed on the system. We didn’t include system utilities such as updaters, since this software serves an important purpose for end users. However, things like trial versions of antivirus solutions, third-party widgets, and other marketing-focused software were considered to be bloatware.

Security

We determined how secure each system was out-of-the-box, and how vulnerable end users are to attacks after simply purchasing and turning on their systems.

Response

Everything has security vulnerabilities, this is a fact. However, how a company responds to reports of security vulnerabilities makes a huge difference. For this category, we judged each vendor on how responsive their teams are when vulnerabilities are reported to them.

Common Themes

The first commonality we noticed was that all of these systems, with the exception of the Microsoft Signature Editions, come preloaded with a suite of McAfee software used to provide host-based firewall, intrusion prevention, and antivirus to each system.

The second commonality was that each laptop had software added by the OEM vendors, including the Signature Editions. However, the Signature Editions were, by far, much cleaner installations of the operating system.

Third, we found that every single laptop had multiple security and privacy issues.

Issues

We’ve already mentioned the eDellRoot issue, but we fairly quickly found so many potential issues to explore that we had to adjust the scope of our searching.

The network traffic was analyzed, mainly during the first few minutes after unboxing and booting up. This rapidly morphed into a combination of network-focused as well as privacy-focused analysis. The paper Bring Your Own Dilemma has all the details, including mitigation efforts.

As mentioned, as one might be lead to assume that since Signature Editions are marketed as “Microsoft-only” software it would mean a complete absence of anything written by the OEM vendors, but this was not the case. Not only did OEM bloatware show up on the Signature Models, with minimal digging, several flaws were encountered. Details can be found A Security Analysis of Signature Edition Laptops.

As mentioned, these seemed to be target-rich environments. We could be looking at this stuff for ages and uncovering tons of bugs. So even after limiting the focus to bloatware updater programs and services, issues were found with every single OEM vendor. The gory details can be found in Out-of-Box Exploitation: A Security Analysis of OEM Updaters.

The security issues varied in scope, complexity, and likelihood of exploitation, but none of the laptops were secure out of the box. Many issues made other issues appear worse. For example, if there is a remote code execution issue dependent on being able to hijack the network, it becomes more serious when the same laptop is trivially vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks via multiple vectors.

Vendor Responses

While we found issues with every laptop, we contacted only four of the vendors. The Microsoft issues were considered “forever day” bugs in that they are in the underlying network protocols added specifically to improve the user experience, and have been discussed for months and even years in various security circles as problematic.

With Dell, the main issue we found was made public and the rest we found were silently patched before we could report them. Of the four we contacted, some vendors responded better than others, with Lenovo and HP rising above the others. See more detail about our experience in Working With OEM Vendors: Vulnerability Disclosure.

Mitigating Strategies

Out of the box, all laptops running Windows 8.1 and 10 immediately contacted Microsoft servers to install the latest security patches. Most of the OEM vendors’ products did the same for their bloatware. But we do recommend looking over the mitigation sections of all the papers referenced, which will bring the laptops up to a decent level, and un-install as much of the bloatware as possible.

Conclusion

Here are the general thoughts for each OEM laptop, bearing in mind all laptops had Windows privacy settings and network configuration issues:

Acer

The bloatware revealed two CVEs, and a fairly unimpressive showing from a vendor response perspective. We felt with more effort it would be easy to find more flaws. Avoid. This was bottom of the heap.

Asus

Very similar to Acer, with two CVEs and an unimpressive vendor response. Again, we also thought it would be easy to find more flaws, and again, avoid. Tied with Acer for last place.

Dell

Maybe Dell learned something from the eDellRoot debacle. Maybe things will get better. Multiple bloatware bugs (more than Acer and Asus) were found, but these were silently patched and they did not notify users about those bugs.

The exception was the notification regarding eDellRoot, which was understandable since Twitter went nuts and dozens of press outlets had a field day writing about it. Time may show they learned their lesson, but right now from a security perspective, we feel avoidance is the best policy. In the middle of the pack, third in a five person race is not great.

HP

These guys had the most bloatware bugs, but did respond and were fixing them. If you must, get the Microsoft Signature Edition, and follow the mitigation advice in the “Bring Your Own Dilemma” paper. Had they responded with some CVEs or customer notification (and had less bugs) they might have tied for first. Second place.

Lenovo

The bloatware bugs existed here, but after we released the “Bring Your Own Dilemma” paper they actually reached out to us. And while one of two bloatware updaters on the Lenovo had problems, the other one at least on the surface looked like they are heading down the right path. We did not look at their Microsoft Signature Edition, but we’d recommend that box and those “Dilemma” mitigation steps.

Out of the five, Lenovo placed first. We guess they really learned something from the whole Superfish nightmare, and have obviously been making positive changes. Frankly they surprised us, we didn’t have them pegged to win.

In general, we would warn users away from using the normal OEM built systems and recommend that they consider Microsoft Signature Edition instead. While not perfect, they were by far better than their counterparts.