What is SAML? The beer drinker’s guide

What is SAML, and why does it exist?

There’s often a knowledge gap in IT organizations when it comes to understanding how exactly the Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) protocol works. Many administrators and engineers are familiar with traditional network-based authentication protocols like RADIUS, LDAP and SSH, but reliance on SAML will increase as organizations continue to transition to cloud-based vendors and services.

This blog post is intended to remove the mystery from SAML authentication, explain the mechanics behind some of the most common SAML use cases, and draw parallels to the unfortunately-fictional BaaS – Beer as a Service, that is.

Simply put, SAML is a protocol for authenticating to web applications. Federating identities is a common practice that amounts to having user identities stored across discrete applications and organizations. SAML allows these federated apps and organizations to communicate and trust one another’s users.

SAML provides a way to authenticate users to third-party web apps (like Gmail for Business, Office 365, Salesforce, Expensify, Box, Workday, etc.) by redirecting the user’s browser to a company login page, then after successful authentication on that login page, redirecting the user’s browser back to that third-party web app where they are granted access. The key to SAML authentication is browser redirects!

What is the difference between SAML and SSO?

If you think of single sign-on (SSO) as “one password to rule them all,” think of SAML as the glue that binds them all together. SAML SSO provides a user-friendly, secure way to access applications or services that doesn't require multiple logins or authentications.

SAML is most frequently the underlying protocol that makes web based SSO possible. A company maintains a single login page— behind it an identity store and various authentication rules— and can easily configure any web app that supports SAML, allowing their users to log in to all web apps from the same login screen with a single password. It also has the security benefit of neither forcing users to maintain (and potentially reuse) passwords for every web app they need access to, nor exposing passwords to those web apps. Once users are authenticated, they are trusted by all service providers within the SAML SSO ecosystem.

How does SAML work?

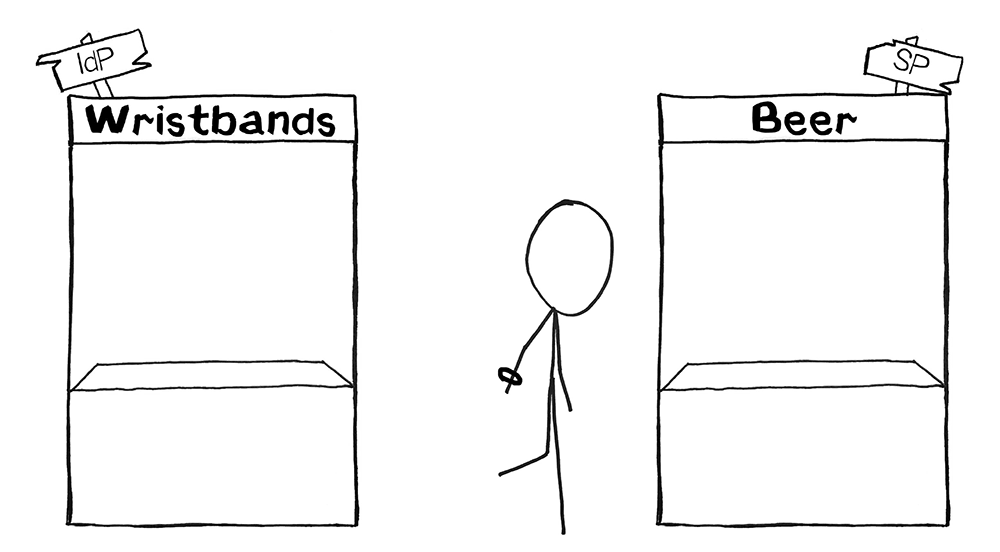

Let’s start with an example of Beer Drinker Bob, who wants to buy a beer at a concert. Beer as a Service:

Bob first walks over to the Wristband Tend, where his ID is checked and a wristband is provided. The Wristband Tent is the identity provider; its purpose is to verify Bob’s identity and make sure he meets the necessary criteria to get a wristband.

Next, Bob walks over to the Beer Tent. The Beer Tent guy sees Bob’s wristband and hands him a beer. The Beer Tent is the service provider; it’s providing the thing that Bob ultimately wants access to—beer!

Now for an example with Software User Stu, who wants to log in to Salesforce. Software as a Service:

Stu first navigates to a dashboard his company has configured, where he’s asked to authenticate (username + password + two-factor) and then can see all the applications he has access to. The login process and dashboard are part of the identity provider; it’s main purpose is to verify Stu’s identity.

Next, Stu clicks on the Salesforce icon and is signed into Salesforce. Salesforce is the service provider; it’s the thing Stu ultimately wants access to.

And that’s SAML in action! Thanks to SAML single sign-on, Stu logged into his company dashboard and automatically had access to every cloud app his company uses, including Salesforce. When Stu clicked on the Salesforce icon, his company's identity provider generated an SAML assertion (a message asserting his identity), his browser navigated to Salesforce, and finally Salesforce validated that SAML Assertion and granted him access.

SAML protocol explained

In SAML lingo, what happened? Let’s start by defining some terms:

Identity Provider (IdP) — The software tool or service (often visualized by a login page and/or dashboard) that performs the authentication: checking usernames and passwords, verifying account status, invoking two-factor, etc. This was the Wristband Tent.

Service Provider (SP) — The web application where the user is trying to gain access. This was the Beer Tent.

SAML Assertion or SAML Token — A message asserting a user’s identity and often other attributes, sent over HTTP via browser redirects. This was the wristband itself.

While SAML doesn't require Security Socket Layers (SSL) or Transport Layer Security (TLS) to work, its widespread practice adds a layer of security between IDP and SP communications when configuring SAML single sign-on.

Step 1 explained: How Drinker Bob and Software Stu authenticated with SAML

This step is where authentication by the IdP happens.

For Bob, authentication entailed the Wristband Tent checking to make sure he was who he said he was (his face matched the picture on his ID) and making sure he met the requirements (he was of drinking age).

For Software User Stu, authentication entailed checking his username and password, making sure his account was active, and invoking two-factor authentication to make sure he actually was who he said he was.

This is a good time to explain that it’s best to think of the IdP as a role in the SAML authentication workflow, relative to the SP. The IdP is simply an authority that the SP trusts. What specifically the IdP does to verify a user isn’t of concern to the SP. The SP only cares if its one-and-only IdP approves of the user and issues an SAML token.

What the Wristband Tent does to verify a drinker’s identity before giving out a wristband is of no concern to the Beer Tent— they only care if the drinker has a wristband or not. The Wristband Tent could require each drinker to present a driver’s license, passport, proof of residency, turn their clothes inside out, then do 20 pushups.

It could even require they visit another tent— maybe a Necklace Tent - then return to the Wristband Tent wearing a necklace to get a wristband. The Beer Tent has no idea about any of this, nor does it care. The only concern of the Beer Tent is whether a drinker arrives with a wristband.

Again, what the IdP does to verify a user’s identity is of no concern to the SP, Salesforce. Typically, IdPs ask for a user’s credentials, but they can also ask for certificates, invoke two-factor authentication, require the user be on a particular network—and, you guessed it, they can even redirect the user somewhere else to have the user pass yet even more tests. What an IdP does to verify a user’s identity is configured by the user’s company and can be influenced (or limited) by capabilities of the IdP solution itself.

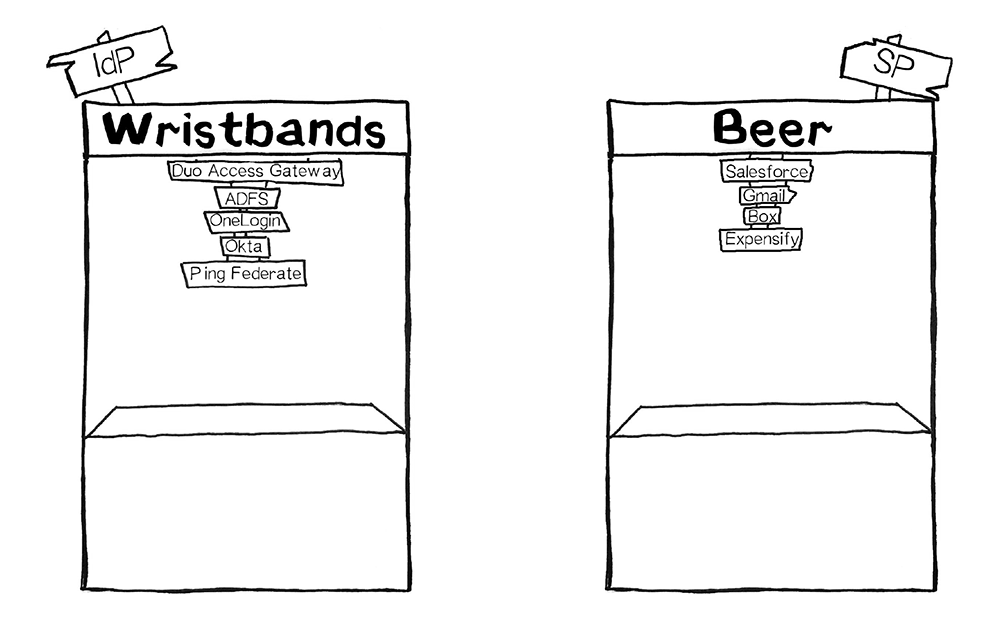

Thinking of the IdP as a role can be helpful for understanding that many products on the market today fulfill the role of IdP. Duo Access Gateway, Microsoft AD FS, Okta, OneLogin, Ping, Centrify and Shibboleth all serve the role of the IdP, to name a few.

After the user is successfully authenticated, many IdP products then display a dashboard with tiles or icons of all the SPs available for that user to click on and be logged into. In our example, Stu clicked the Salesforce icon, which told his IdP to generate a SAML assertion for Salesforce that adheres to all of Salesforce’s requirements: what attributes need to be included in that assertion, and how it should be formatted for Stu to successfully gain access to Salesforce.

Step 2 explained: How Bob and Stu were granted access

This step is where verification of the SAML Assertion by the SP happens.

For Bob, verification entailed the Beer Tent checking to make sure his wristband was legitimate and issued by the Wristband Tent they trust.

For Stu, verification entailed Salesforce checking the SAML assertion to make sure it came from the IdP that Salesforce trusts. In addition to checking the authenticity and validity of the SAML assertion, Salesforce also looks in the SAML assertion to see who Stu is and who he should be logged into Salesforce as.

There are often many SPs configured to a single IdP. So, while Stu went to Salesforce this time, maybe next time he’ll go to Gmail and his company dashboard (IdP) will generate a different SAML assertion that adheres to Gmail’s requirements. This is like having many different tents— a Wine Tent, a Liquor Tent, and our favorite Beer Tent—all who trust a single Wristband Tent. The Wristband Tent can issue a different wristband for each of the Wine, Liquor or Beer Tents depending on where the drinker wants to go.

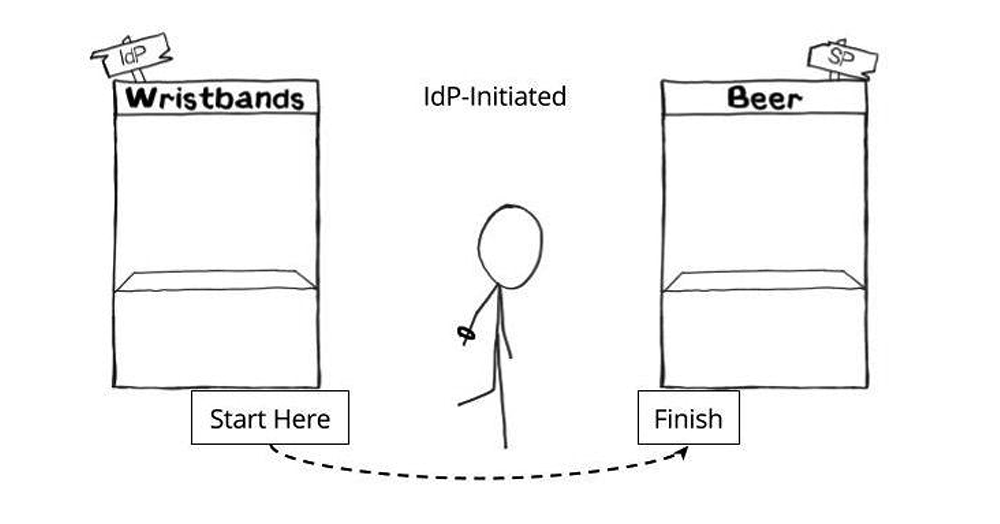

IdP-initiated vs. SP-initiated

IdP-initiated versus SP-initiated refers to where the authentication workflow starts. It’s often asked about because some service providers support SP-initiated logins while others don’t. What’s unique about the SP-initiated login is a SAML request.

An IdP-initiated login starts with the user first navigating to the IdP (typically a login page or dashboard), and then going to the SP with a SAML assertion. This is like first going to the Wristband Tent, then going to the Beer Tent after having received a wristband. The examples above where a user is logging into Salesforce and getting beer were both IdP-initiated.

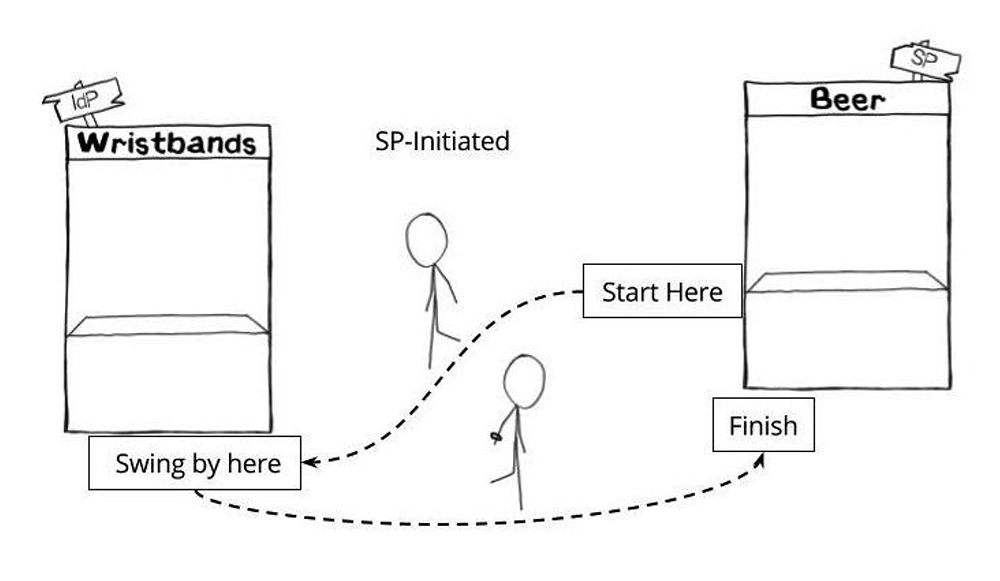

An SP-initiated login starts with the user first navigating to the SP, getting redirected to the IdP with a SAML request, then redirected back to the SP with a SAML assertion. This is like first going to the Beer Tent, getting sent over to the Wristband Tent because you don’t have a wristband, then returning to the Beer Tent when you do have a wristband.

Why does this matter, and what does it mean? What is a SAML Request? It matters because these redirects (go to the Wristband Tent, then come back to the Beer Tent) require that the SP issue a SAML request. A SAML request says, “This user is trying to log in, but they don’t have a SAML assertion yet. Please help them get a SAML assertion, then send them back here.”

However, not all SPs can issue SAML requests, which limits logging into that SP only as IdP-initiated. (And seriously, SPs, if this is you it’s time to join the party.) A SAML request is like someone going to the Beer Tent without a wristband, the Beer Tent writing a note saying, “This guy wants beer. Give him a wristband and send him back,” pinning the note to his shirt and shoving him toward the Wristband Tent. It makes it easier for people who like to drink beer, and that’s why we prefer it.

How to set up SAML

We’ve covered the basics of what SAML is, how logging in with SAML works, and a few of the most common SAML scenarios. Now, let’s talk configuration specifics: setting up the tents.

Configuration for SAML integration must be done in two places: at the IdP and at the SP.

The IdP needs to be configured so it knows where and how to send users when they want to log in to a specific SP. This is like setting up the Wristband Tent and making sure its workers know they’re checking IDs so that people can be served beer (and that they shouldn’t let minors have a wristband), and after they issue a wristband to point people toward the Beer Tent (rather than, say, a T-shirt Tent or out of the concert venue).

The SP needs to be configured so it knows it can trust SAML assertions signed by the IdP. This is like setting up the Beer Tent and making sure its workers know to look for wristbands that match the wristbands that their trusted Wristband Tent is issuing (as opposed to a friendship bracelet someone just happens to be wearing).

IdP configuration

Specifications for a SAML assertion - what it should contain and how it should be formatted - are provided by the SP and set at the IdP. This is like the Beer Tent dictating what they expect to be on a wristband and the Wristband Tent being made aware of those expectations.

The following values must be set at the IdP for each SP, and there’s often quite a few of them. This is like a Beer Tent, a Whiskey Tent and a Wine Tent all trusting the same Wristband Tent. Often, IdP products can set these automatically behind the scenes, but as an admin you’ll need to provide at least some of this information:

EntityID – A globally unique name for the SP. Formats vary, but it’s increasingly common to see this value formatted as a URL.

Real Example: <EntityDescriptor entityID="https://beertent.com/concert">

Beer Example: “Greg’s Concert Beers”

Assertion Consumer Service (ACS) – The URL location where the SAML assertion is sent.

Real Example: https://beertent.com/saml/consume/

Beer Example: “Arrive at the left side of the Beer Tent. That’s where the line starts.”

ACS Validator – A security measure in the form of a regular expression (regex) that ensures the SAML assertion is sent to the correct ACS. This only comes into play during SP-initiated logins where the SAML request contains an ACS location, so this ACS validator would ensure that the SAML request-provided ACS location is legitimate.

Real Example: ^https:\/\/beertent\.com\/saml\/consume\/$

Beer Example: “Make sure you’re going to this Beer Tent and not some other tent.”

Attributes – The number of and format of attributes can vary greatly. There’s usually at least one attribute, the NameID, which is typically the username of the user trying to log in.

Real Examples: NameID Format, NameID Attribute

Beer Examples: “The wristband shows your name is Bob Boozer.”

“The wristband shows that was your first name and your last name.”

RelayState – Not required. Deep linking for SAML. This tells the SP where to take the user once they’ve successfully logged in.

Real Example: https://beertent.com/taps/lager/

Beer Example: “After the Beer Tent approves of your wristband, ask for a lager.”

SAML Signature Algorithm – SHA-1 or SHA-256. Less commonly SHA-384 or SHA-512. This algorithm is used in conjunction with the X.509 certificate mentioned below.

Real Example: SHA-256

Beer Example: “The wristband has a hologram, so you know it’s real.”

SP Configuration

The reverse of the section above, this section speaks to information provided by the IdP and set at the SP. This would be the information we provide to the Beer Tent to give them a way to validate that the wristbands drinkers arrive with were truly issued by the Wristband Tent they trust.

X.509 Certificate

A certificate provided by the IdP, used to verify the public key as passed by the IdP in the metadata of the SAML assertion. It allows the SP to verify the SAML assertion is actually coming from the IdP it trusts. SAML assertions are usually signed, however SAML requests can also be signed. Typically, it’s downloaded or copied from the IdP and configured by uploading or pasting it into the SP.

Issuer URL

Unique identifier of the IdP. Formatted as a URL containing information about the IdP so the SP can validate that the SAML assertions it receives are issued from the correct IdP.

Real Example: <saml:Issuer>https://access.wristbandtent.com/saml2/idp/metadata.php</saml:Issuer>

Beer Example: “Only accept SAML assertions that are issued from a Wristband Tent that matches this description.”

SAML SSO Endpoint / Service Provider Login URL

An IdP endpoint that initiates authentication when redirected here by the SP with a SAML request.

SAML SLO (Single Log-Out) Endpoint

An IdP endpoint that will close the user’s IdP session when redirected here by the SP, typically after the user clicks “Log out.”

Real Example: https://access.wristbandtent.com/logout

Beer Example: “Go to this location at the Wristband Tent to have your wristband removed.”

How is SAML different from OAuth and Web Services Federation?

We hear about these other SAML alternatives in passing, but how do they differ? SAML, OAuth, and Web Services Federation (WS-Fed) all vary technically, as well as how they’re best used.

SAML 2.0 – Most commonly used by businesses to allow their users to access services they pay for. Salesforce, Gmail, Box and Expensify are all examples of service providers an employee would gain access to after a SAML SSO. SAML asserts to the service provider who the user is, authenticating their identity.

WS-Fed – Web Services Federation is used for the same purposes as SAML, to federate authentication from service providers to a common identity provider. It’s well supported with certain IdPs, like Microsoft Active Directory Federation Services (AD FS), but it’s not prevalent with cloud service providers. WS-Fed is arguably simpler than SAML for developers to implement, but its limited support among IdPs and SPs alike make it a tough sell.

OAuth – Most commonly used by consumer apps and services so users don’t have to sign up for a new username and password. “Sign in with Google” and “Log in with Facebook” are examples of OAuth in the real world. OAuth delegates access to a person’s Google or Facebook account by a third party.

Typically, the app the user is signing into can directly read information from the user’s profile or take actions (like post pictures or make updates) on their behalf; this is authorization. This would be like going to the Beer Tent and instead of the Beer Tent sending Bob to the Wristband Tent, they ask Bob to hand them his ID and sign off that the Beer Tent workers can go over to the Wristband Tent on his behalf and represent him; he is authorizing them.

What’s more important is to look at the prevalence of each technology for each use case. SAML is ubiquitous in the workplace for cloud-based apps, while WS-Fed is not. Conversely, OAuth is ubiquitous among consumer apps.

What is Microsoft’s approach to SAML?

Microsoft’s Active Directory Federation Services has their own terminology and approach to SAML, so it warrants a short explanation. Microsoft AD FS is an identity provider. Think of it as Microsoft’s solution to the Wristband Tent: tricky to understand if you’re new to the world of Wristband Tents, but very customizable.

Relying Party is the term that Microsoft AD FS uses to mean Service Provider.

Claims Rules is another term that only Microsoft AD FS uses. Claims Rules are just that: rules you can apply to alter how or when to invoke authentication. For example, an admin could set up a claims rule that only applies when a user comes to AD FS as they’re trying to get to Dropbox. Plus, it prevents them from using a mobile device, allowing that user to log in with a laptop or desktop device but not their Android or iPhone. Some IdPs other than AD FS can create similar rules, but AD FS allows for some of the most robust and complex rule creation.

ImmutableID is the Active Directory equivalent of an ObjectGUID. It’s not specific to AD FS, but it’s worth a mention.

WS-Fed is similar to SAML and abides by many of the same rules. It’s a protocol specifically created by Microsoft and not widely supported by IdPs other than AD FS.

How to troubleshoot SAML

The best way to troubleshoot SAML is the same way I recommend troubleshooting most issues: start with the basics.

Scope – Is the issue affecting all users, or just a few? If no users can sign in, that’s an immediate indicator of a service interruption or misconfiguration. If you’re setting up an IdP and SP for the first time, it’s probably a misconfiguration.

Experience – What is the user experiencing that indicates an issue? Is the user getting an error on the IdP login page? Or is the user getting an error generated by the SP after they successfully authenticate to the IdP?

Because SAML “happens” via browser redirects, it’s usually pretty straightforward to determine where a problem is occurring - just look at the URL. If a problem is occurring while on a URL belonging to your IdP, well, it’s probably an IdP issue. Same goes for the URL of your destination SP.

Error at the IdP

For just a few users:

Is there an error message? Does it give us any clues?

Is the username and password valid?

Is the user account unlocked?

Is the user successfully passing two-factor authentication or any other authentication steps?

Try again. Clear cache. Try an incognito window. Try a different machine. Is there a way to isolate and identify the issue?

What do the logs show?

For all users:

Is there an error message? Does it give us any clues?

Is the user able to resolve the URL of the IdP and actually view the login page?

Is your IdP able to communicate with your identity store (like Active Directory)?

If the configurable, keep the authentication flow simple and get one step working at a time, i.e., work to make sure primary authentication is working successfully before moving on to troubleshoot two-factor authentication.

Error when arriving to the SP

For just a few users:

What is the error? Does it give any clues?

Does the user have a valid username within the SP?

Check to make sure the username storied in the SP matches what is being passed in the SAML assertion. My favorite tool for this is SAML Tracer, which allows you to easily view the contents of a SAML assertion.

Does the user need to be in a specific group?

For all users:

What is the error? Does it give us any clues?

Are any users already provisioned within the SP?

What does the SP expect the SAML assertion to look like? What are the required attributes and their formats?

Do all users need to be in a specific group?

Now that we've talked about the ins and outs of SAML, there's just one thing left to say: Cheers!