00. The security industry, unlike others, won't mature

Security is full of Big Problems. These Big Problems keep you up at night; they're visible even to folks outside of the industry; and they change on a regular basis. Over the past couple of years, it's been ransomware. Before that, it was polymorphic malware, or self-replicating worms. Before that, even, it was phreaking. I believe that these Big Problems are just symptoms of other, deeper, Hard Problems; that these Hard Problems have to do with the incentive structure for both the attackers and defenders; and that unless we solve these Hard Problems, new Big Problems will continue to pop up. The existence of these Hard Problems prevents the industry from maturing, but you, my beloved reader, have the opportunity to change it's course towards advancement. This article is my attempt to catalog the evidence of these Hard Problems, convince you that they exist, and discuss ways in which you can make an impact, in your current role, to fight them.

Security is a unique industry. It is immature. It behaves like an industry based on new technologies: regulations (where they exist) are lagging far behind risks, and aren't well-unified across jurisdictions; best practices are evolving; and there are huge information asymmetries across the industry.

Contrast this to the mature auto industry: everyone knows that it's more expensive to insure a 17-year-old with a speeding ticket (sorry mom and dad) than a 40-year-old mother of two in a minivan, and one insurance policy works easily even as you drive in other states or rent a car overseas. There's information symmetry: for the most part, both you and the insurance company know that you're at higher risk of accident because you're a leadfoot, as much as you don't admit it.

Or look at the aviation industry's maturation. At first, it was the Wild West; flight went from impossible, to experimental, to applied, to something that you can do routinely with the family. After some incidents (like when Leonardo DiCaprio pretended to be a PanAm pilot for several years in the 1960s), it became a mature market: damn near every flight I've been on in my life has followed a relatively standard design, according to FAA guidelines based on NTSB lessons learned; and operations are pretty familiar between airlines (seatback TVs and complimentary booze notwithstanding). There's risk observation, cataloging, and quantification: I am very confident that clicking around the NTSB's site would give me an almost completely exhaustive understanding of flight accidents in the United States. I'm quite certain there's no such repository that would show me all cyber incidents.

You get the picture: a new technology is invented, then adopted, and finally reaches some sort of stable point between the technology, the use, and therefore the industry and regulation. I've seen a great deal of writing that assumes cybersecurity will follow this same sort of maturity curve as many other industries have. In the same way that my coworkers have resigned themselves to my sense of humor: I'm afraid it will never mature. Here, I will explore why I believe that this is the case, as well as what I believe these observations mean for the future of the industry.

In section 01, we'll look at security's relationship to the rest of the organization; these incentives matter in the rate of change for Big Problems. In section 02, we'll look at attackers; these incentives also matter in predicting the next Big Problem, and are intended to establish the fact that Big Problems will continue to exist because of these Hard Problems of economics and incentives. In section 03, we discuss some of the reasons that these Hard Problems matter - what we, as an industry, can start to do about it. In section 04, I caveat some of my argument - that we will, and have already, seen improvements and experiments to resolve some of the Hard Problems. In sections 05 and 06, I get more specific about how Builders and Practitioners can take action, and in section 07, I summarize this novella.

01. Some observations about the cybersecurity industry

First and foremost, what am I talking about when I say the cybersecurity industry? I'm talking about all of the activities taken by people who are personally incentivized to address cybersecurity risk in all forms. Specifically, this will include:

Practitioners: those administrators, security analysts, incident responders, and other folks who collect a paycheck from an organization in order to protect that organization from cyber risk. Also defined as "everyone who reports up to the CISO"

Builders: those engineers, designers, marketers, and salespeople who work for security vendors which build the tools used by Practitioners. Also defined as "everyone who said Generative AI too many times at RSA this year"

Policymakers: those lawmakers, lobbyists, thought leaders, and the wonderful, wonderful souls in standards working groups who make it possible for the rest of the cybersecurity industry to all work together & make large-scale, long-reaching decisions about the industry. Also defined as "people who can cite NIST draft sub-paragraphs from memory"

Attackers: this is a subgroup, to be sure, and I'm not inviting them to the party. But they're an important group because they set the pace for the rest of these folks. A much younger Joe was taught this lesson by a martial arts instructor who told me that "the adversary sets the pace" (he then choked me). Also defined as "the core user group for cryptocurrency"

The security industry, of course, extends far beyond these interested parties. I've completely left out all of the overworked help-desk workers, all of the end users who get impacted by security on a daily basis, everyone who's ever been hired for one job—often in IT—and then onboarded to find out that "security is also their responsibility." I'm focusing our conversation here on those interested parties who are active enough in the industry to wield strong influence. In other words, those parties whose motives we can reasonably assume will change the development of the industry.

For purposes of this article, I'm largely going to focus on the incentive structure for attackers; this drives the threats that practitioners need to react to, and that builders need to, well, build for. And the pace of change from attackers means that policymakers are always fighting an uphill battle. This makes things harder for practitioners and builders.

Security is a Risk Mitigation Industry

Let's start with this: security is a risk mitigation industry. It does not, in and of itself, have any value. There's no seatbelt market without cars; nobody wants to tie themselves to couches quickly. What does exist, on the other hand, is a mobility market: people want to get around, and therefore they buy cars. There's a seatbelt market because people want to get around… while dying less often.

This matters because of security's relationship to the resources which we protect. Cybersecurity is an industry based on mitigating risks around the confidentiality, availability, and integrity of information systems, the data which they hold, and the real-world impacts that they have. Therefore we see another source of change: security will have to adapt every time that there's a new type of technology, every time that there's a new type of data that becomes commonplace; and every time that there's a new way for technology to impact the world. There's no ransomware trend without cryptocurrency being widespread, normalized, and liquid; there's no data extortion trends without sensitive data becoming core to business functions; and there's no stuxnet without SCADA systems controlling critical machinery. As cloud computing offered an opportunity to move CAPEX into OPEX, it became more popular; as that happened, new attack techniques became more popular, targeting these new SaaS resources over legacy on-prem attack types which had been well studied and documented.

This dependency on the rate of change of the technology world matters because technology is almost defined by its rate of change. This year alone, almost all of the S&P 500's gains have been driven by the 'AI wave'. Doctors kept giving shots; rail companies kept moving freight; restaurants continued to serve food. But the tech sector itself changes rapidly - much quicker than others. That's a reasonable definition for the technology industry itself- the new stuff. Look, for instance, at the relative R&D budget for technology companies compared to any other sector (pharmaceuticals perhaps notwithstanding); at the areas in which companies are filing patents; at the existence of the entire VC industry, and what investments it focuses on. As a result of this rapid rate of change, widespread adoption, and deep integration with so many critical business systems, technology is also extremely sensitive to shocks in human behavior. Take COVID work-from-home, the resultant changes in adoption to remote work tools like video conferencing, remote signing, and collaboration tools; and then the resulting trends in threats like increased initial access attempts and BEC scamming.

Technology moves fast; security is implemented reactively to these changes in technology. For that reason, security is unique among all risk mitigation industries, in that it must adapt at a much higher rate. This gives practitioners much less opportunity to develop, refine, and drive adoption of best practices; this gives policymakers much less opportunity to learn about new, complicated topics and develop robust policy to them; and it gives insurers much less opportunity to identify, catalog, and develop actuarial tables out of security mitigations and risk factors. Without any obvious changes to these core Hard Problems, we can expect to see more Big Problems, such as new threats that defenders aren't well-equipped to deal with, that policy makers are ill-equipped to respond to; and that insurers are ill-equipped to predict resulting costs. This is a description of an immature industry.

(Aside: I've always thought that "the CIA triad" would be a sick phrase in some sort of intelligence agency thriller about a hidden tribunal but alas, it's only chapter one in every security book. Lame)

Mitigating Risk is Costly

Now, on those systems which we protect: most of them exist to serve some profit-driven end. And so the folks in charge of them (CIOs, CTOs) are incentivized not just on top-line budgets (e.g. selling more stuff) but also on bottom-line budgets (e.g. spend less to sell that much stuff). When business managers are looking at budget allocation, security is a cost-center; and the squirrely, black-hoodie-cloaked, jargon-filled, technically intimidating, I-think-that-guy-can-read-my-emails department of security does not often have a clear way to show "here's all of the money you didn't spend on disaster recovery last year because of the investments you made in security."

Add into this that it's very difficult to predict security value ahead of time. Vendors are constantly trying to find ways to communicate this; buyers are constantly trying to validate that. Security is a market for silver bullets. Security teams are inundated with new threat types on a regular basis, and are constantly reacting to new changes to the business functions and technology stacks which they're charged with protecting; accurately predicting the threats that they must prioritize is extremely difficult. This gets back to the fact that best practices in the security industry (with several clear exceptions) are very difficult to establish and maintain.

What's much more clear is that the security team is spending a bunch of money on a bunch of stuff. None of that money is ending up as profit. The lack of visibility for security's value, compared to the clear visibility of security's cost, is a persistent theme that practitioners struggle with and is part of the reason that security teams around the world struggle with funding.

There have been some changes to this: the SEC (among other bodies) has led the charge by requiring that breach notifications are reported. This requirement, and its cousins, do a few things:

They force the organization to try and quantify the material effect of the breach, in total. The SEC is doing this, again, from the perspective of the investor, who doesn't particularly care whether you spent money on PR or legal fees or ransoms or leading DFIR companies, so much as they care that you spent money that could have gone back to them for their retirement fund

They drive accountability, in that someone has to sign that disclosure, and not many folks whose career has risen to the point that they're signing off on SEC filings is legal-risk-tolerant enough to lie on it

They drive more visibility: business managers & investors are more likely to read an 8-K filing than something on your security.acmecorp[.]com/noindex/norobot/securityadvisories/ blog

There are other trends, here, too, such as some of the legal theory that's been used to assign accountability in the wake of the SolarWinds attack. The CISO job is impossible and stressful; however, if the industry adopts to a realized level of accountability for executives (and I include, there, more than CISOs - CIOs, CTOs, chief council, and CEOs come to mind) then perhaps incentives will change. "I will not take this job if you continue this policy" becomes a pretty strong argument when the person saying it can point to three peers who've just visited prison for making the wrong call in similar scenarios.

In addition to the poorly-defined and even-more-poorly-predicted material costs of breach, there's the pervasive issue that we, as a society, have become inured to the constant barrage of unacceptable attacks. The breach notifications write themselves: In or around November or February, 2018/24, we detected suspicious activity within our system. I will be honest with you: I have no idea how many credit monitoring services I subscribe to. I kinda gave up after 2015 when a very detailed accounting of my 'Psychological and Emotional Health,' 'Illegal Use of Drugs and Drug Activity,' 'Use of Alcohol,' 'Financial Record,' and other topics was consolidated and leaked. I know I'm not alone in my nihilism, nor is my data remotely the worst scenario I've heard of.

Security as Accountability

The cybersecurity industry is largely defined by the roles of the people who work within it: who's a buyer, who's a user, and who's a builder of security tools. These roles are defined by the results and efforts for which they are accountable. In other words, it doesn't matter what changes in technology, or threats, or business behavior that come down the pike: a CISO is a CISO because they're the person who is responsible at the end of the day. A SOC is a SOC because they're supposed to detect bad things and react to them. Note that these 'bad things' and 'responsibilities' are purposefully vague, since they can apply to everything from an unauthorized person walking into your building to a new quantum-based, crypto-breaking development to some niche threat I've never heard of.

This matters because several relationships will likely remain constant in spite of radical changes in technology, threats, and business models. A CISO is not defined by the fact that they are or are not a Splunk shop, or whether they are an on-prem shop or have completely migrated to the cloud, or even what type of data they're protecting. No. A CISO is defined as the head that rolls if something bad happens, full stop. You can make similar arguments for builders, too: they're the ones who are accountable for delivering on revenue driven from selling solutions to security problems, even if those problems change or disappear or new ones materialize.

This means that the people, titles, relationships, and overall structure of the cybersecurity industry will remain constant in spite of the many of the changes that are taking place within it. Put differently: I don't think that the security industry will be supplanted by some other industry, even if there are major changes in the source and type of threats, the types of technologies and techniques used to defend against them, or the motivation and end goals of the threats themselves; I think it will continue to exist, albeit under a state of constant change.

In the Cold War, there were arguments to defund or even abolish some of the services - namely, the Marine Corps - since technology (here, technology meaning nuclear weapons, ICBMs, and SLBMs) had progressed and the Air Force could just "do" all of war. This never happened. The Marine Corps continues to exist, their mission set distinct from those of any other branch, since they were accountable for the United States' ability to forward deploy agile, independent, amphibious infantry. What they've done - instead of being supplanted - is adapt to this new environment, in which USMC doctrine has been updated to deal with nuclear threats and warfare. What I'm arguing here is that the security industry (metaphorically, the USMC) will continue to exist, it will just adapt to a new world in which it also deals with new threats.

Hidden Incentives

Cybersecurity has a unique set of moral incentives. In large part, there is a mission-driven purpose that motivates a lot of folks to work in the industry—it feels good to do the right thing. You see this in other industries, too: everyone I know who works in healthcare did it, at least in part, to help others. What's unique about cybersecurity in this regard is that this mission-oriented motivation is unable to be expressed by sharing best practices or discoveries in many scenarios. Doctors who have a unique patient, even if that patient eventually has a bad outcome, will often write about them in journals (the New England Journal of Medicine, one of the premier medical journals, has a section called Clinical Trials Case Study specifically for this type of thing).

In cybersecurity, there are often legal incentives that prohibit this type of knowledge sharing. After a breach, any third party whose information was affected—often customers, but also partners, employees, and others—is, at least in the United States, liable to pursue legal recourse. Companies who have been breached don't want to give tacit admission of guilt for negligence, and therefore a thorough post-mortem is rarely published, and sometimes not even recorded (final versions are delivered internally, verbally, such that there is no existing record to pop up in discovery). There is legal risk involved in incident response reports, due to common law decisions in US courts. Public relations and legal advice tells the security team to hush up, or not even create, a post-mortem or incident response report. This robs all industry peers from learning, up-close-and-dirty, how they can better protect themselves. That is a dark pattern, and a shame. Exceptions to this, where they happen - like the British Library's report on their 2023 incident, or CISA's scrubbed report on a recent engagement, are incredibly helpful to inform strong defenses. Third parties, like MITRE, Cisco Talos, Verizon, and many others, close this gap where possible, but there is no substitute for first-person, detailed, broadly shared responses (like those you might find in a mature industry, such as transportation).

Finally, not all industries share dual-use technologies with the most well-funded intelligence agencies in the world. This is an aside, and not the intent of this article, but it would be remiss not to mention the fact that the state-sponsored market for surveillance tools, the activity of nation-state actors in commercial enterprises, and the crossover in motivation and attribution that so often occurs in advanced incidents, all have a significant impact on the direction of the security industry.

02. Some trends we see in attacks—and what they tell us about the future of the industry

At the end of the day, the rate of change in the technology industry wouldn't matter to security if it weren't for the active, highly incentivized, capable threat actors who are responding to these changes to find new, or improve existing, techniques. Here, I'll lay out some of the trends that we can see - and what incentives we can infer from them. This is an argument that the Big Problems we see come and go are more indicative of Hard Problems of incentive and ability, which will, in combination with the rate of change of technology, keep security from establishing an equilibrium.

There have been a million articles about how "professionalized" threat actors have become. This is (a) true; (b) not just a truism, and (c) important to how we view the threat landscape. I don't think that a bunch of threat actors just finally got their hands on A Wealth Of Nations and were like, "bro, we're like, a cyber pin factory, we should totally specialize as such". But this 1776 Adam Smith quote—aside from overusing "peculiar"—could literally have been written last month about the professionalized threat actors:

But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades.

What has happened? Threat actors (and here, I'm focusing on financially motivated ones, though there are certainly some very gray lines in that classification) have increasingly organized themselves. These organizations have been remarkably successful in increasing the overall productivity of their actions; ransomware has become a multi-billion dollar industry largely due to these changes. Said organizations have been a spectrum from "some teenagers who share tips about brute force attacks in telegram channels, or sim swap techniques in songs" to organizations that are nearly indistinguishable from an above-board company with legal entities, benefits programs, and HR departments. This organization has largely been horizontal - individual actors are combining their knowledge and similar techniques to improve their overall efficacy. What has been most interesting & impactful is the vertical integration and coordination that this has often facilitated: one successful attack might be accomplished by an IAB, then a lateral movement expert, finally a ransomware strain is licensed, and ultimately a customer-service rep conducts negotiations.

Why has this happened? Honor among thieves is hard to come by. As a digital ne'er-do-well, you're more likely to stay out of the clink by staying as anonymous as possible; this leads to you acting alone wherever possible. However, there's always been incentive to work together (haven't you ever seen Oceans 11? Every successful criminal crew must be a motley crew of colorful personalities with diverse skill sets). Ask any above-board red teamer (assuming they've got time to reply to your message between engagements, reports, and constantly staying on top of new learning): it is hard to stay abreast of all of the latest exploits, patches, techniques, and detections. It's much more productive to spread out expertise among the different stages of an attack, and that's exactly what we've seen happen.

This has been enabled by a couple of trends. First and foremost, cryptocurrency has been an incredible market-maker for anonymous deals on the far side of the law. While I rely on small claims court & Google reviews to enforce the deal that I made with my landscaper, criminals don't have the luxury of relying on institutions like "the law" or "the court of public opinion." Crypto solves the zero-knowledge problem: it's available worldwide, and as it's grown in popularity, it's become much more liquid making it very easy to convert crimes into goods. Laundering this money has gotten easier and easier.

Secondly, geopolitical forces are at play: in a number of high-profile countries, one can be well-known as a "hacker" to the authorities and remain unmolested, so long as you play by their rules (usually, don't target anyone domestically, give us information when you have it, and occasionally do a job or two for us).

And finally: the market has continued to develop itself. Monetization solidified around ransomware for a couple of years, which was two things: profitable and complicated. The profit incentive motivated threat actors to organize; the complicated nature of an attack - which requires, at minimum, recon, initial access, lateral movement, privilege escalation, deployment, execution, negotiation, and laundering of funds, all of which require different, difficult skills on different systems—made specialization and commercialization of "as-a-service" attacks a clear way to improve one's odds of success and profitability.

This has led to a series of product improvements in which ransomware operators, Initial Access Brokers, and other organizations have productized their wares. They're more reliable; they come with better support; they're clearly described and reviewed; they're more transactable. All of the techniques that make you more likely to buy something innocent online are used to improve the chances of another sale of cybercrime. The improved market has reduced friction further, lowering the barrier to entry, and increasing the volume of attacks.

What does it matter? This matters for a few reasons. First, we can expect that "developer velocity" will increase for attackers as specialization continues. When initial access used to be 10% of your job, and it's now 100% of your job, we can expect that you're going to get better at initial access at a higher rate. The same argument holds for all points in the attack chain. This same increase in "developer velocity" can come from the network effects of many attackers coordinating their efforts. At no modern company do we set up ten engineers to work independently from each other on the same problem; we know that the problem will be solved more quickly when those engineers are able to coordinate, share ideas and learnings, bounce ideas off of each other, and yes, specialize.

It also means that we can expect other ways to disrupt this threat activity. A truism my grandpa would have known in his bones, if not by attribution: "It takes a lifetime to build a good reputation, but you can lose it in a minute." Now, I don't know what Will Rogers knew about cybercrime, but I think he hit the nail on the head—trust is hard to earn and easy to lose. There have been a number of successful disruptions to criminal groups by planting the idea that trust has been lost, which then erodes trust and the efficacy of said group (Opie's character arc in Sons of Anarchy notwithstanding).

More recently, economists have modeled trust as an efficiency-building mechanism. It's cheaper for me to buy, say, a car from you if I trust you. Then I don't have to validate everything myself with an independent inspection. This is directly related to all of the economic productivity gains that come from a clearly established rule of law, international standards (shoutout ISO), and moving to a market of efficient goods in which buyers and sellers have full information.

Do we expect it to continue? Clearly, I don't have the most convincing track record for predicting the future, but sure, let's dive in. Those elements to which we attribute the growth of the underground market —cryptocurrency, law enforcement (or lack thereof), and profit incentive—all still exist and don't show signs of changing in the immediate future. Even if you accuse me of re-predicting the end of history, I do believe: in the immediate term, the core functions are likely to continue to function, at least nominally, for a couple of years.

With that said, all of these elements have some emerging trends that could significantly change their outcomes, which brings us to:

What can we do about it? First, the more we're able to centralize all of this horrifically dystopian, coal-powered fiat neat little science experiment of crypto, the better law enforcement will be able to drive down trust in the anonymous properties thereof. There have been some operations to varying degrees of success (and it's not just the US doing this); whether this continues as a cat-and-mouse game of laundering techniques or develops into a significant change in the operating model of cyber threat actors remains to be seen.

Second, law enforcement can, you know, enforce laws. I don't think that Mongolia's northern and southern neighbors are going to suddenly change grand strategy and grey zone tactics; I do believe that there are plenty of threat actors operating outside of those borders, that defenders are improving their abilities in attribution, and that law enforcement is adapting to newer trends.

Finally, defenders have a say in this, too. As immutable backups have become more common, there are starting to be some signs that ransomware is becoming a less frequent, but higher-impact, problem. As this has happened, attackers have explored other forms of monetization that create a shorter, straighter line from attack onset to monetization; BEC wire scams, data extortion, and resource theft (crypto mining never died) are all examples of this kind of trend. Now, this does create some amount of circular reasoning: who cares if we've gotten rid of the highly efficient criminal markets if criminals have just moved on to…highly efficient independent operations? That said, I believe that the benefits of a market listed above—specialization and coordination—persist regardless of monetization technique, and therefore getting rid of markets is a win for defenders, full stop.

Attackers Are Rational Actors

Threat actors are morally wrong in their actions. They kill people. A conversation about the topic that papers over this rings hollow. However, keeping the moral lens on for our entire analysis also blinds us to a lot of useful information. So, for now, bear with me as I view attackers as rational actors (those neat, tidy, little Homo Economicus so that we can derive some insights—perhaps even make some predictions) from their incentive structure.

Attackers Are Incentivized To Pursue Those Attack Routes With a High Probability of Success

This is no surprise. We all do this. "Have a backup plan," "apply to safety schools," "don't you think that's a bit ambitious for you?" "hm, maybe we should consider a different option given your performance." We've all heard this from guidance counselors and bosses throughout our careers. Right? Like all of us, right?

Anyway.

Financially motivated attackers aren't, for the most part, drug-dabbling insomniacs who work for E Corp; they're mostly people with bills and stuff. This has limits, for sure (there are definitely blurry lines between hacktivism, financial incentive, and doing it for the lulz) but they're largely looking for scores that will reasonably pay. And that's why we see a lot of small-town dentists getting hit, even while a successful ransomware attack on Google or the Pentagon would (theoretically) pay much more—they're looking for the lower-hanging fruit, for the easier options, for the scores they know they're able to get. Many financially motivated attackers are largely opportunistic in nature. And since security developments are largely led by a smaller group of well-resourced companies, this means that attacks will continue to succeed on those industries that have been victimized historically. Smaller organizations, especially in lower-margin industries or those with limited IT budgets are at risk: manufacturing, healthcare, and higher education are big here.

Attackers Are Incentivized To Pursue Those Attack Routes With a High Payout

This is different from high probability of success! Remember Stats 101? Expected value = expected payout * probability of that payout. Betting on a color in roulette instead of a number in roulette type of thing.

And this is why there's always going to be a part of the criminal market who at least attempts to go for the whales: the big, well-defended, well-funded organizations. There are a whole host of examples, but we should also keep in mind some of the second-order effects that criminals have in mind, as well. Two that I'll highlight: BATNA in ransomware negotiations and supply chain attacks.

BATNA (or, what happens to you if you don't pay up) is predictably higher for organizations who would later be subject to significant costs other than a ransom payment. These can be in the effect of business operations interruptions (as Clorox's recent experience shows, this can be significant) or in the form of lawsuits from affected parties, largely customers (which can also be very expensive). So we should continue to expect to see ransomware targeting those industries where data interruptions cause business disruptions (which in today's state of "digital transformation" means just about everyone; but there are levels here, and the more vulnerable an organization is to operational disruption due to IT disruption, the more likely they are to be targeted by ransomware, all else being equal). In immediately recent memory, by way of example, there were widespread shutdowns in auto sales due to an incident of this type. We should also expect to see both ransomware and data extortion attacks targeting organizations with large amounts of customer data.

Unfortunately, this means we should expect to see significant attacks on healthcare.

Attackers are incentivized to pursue those attack routes with a low risk of legal repercussions

"Criminals don't want to get in trouble." Wow, Joe, so glad I've read this far for such enthralling insights. But, my beloved reader, this basic assumption matters quite a bit. We can create an incentive structure through the ways in which defenders & law enforcement behave, and especially in the way that they cooperate with each other. CISA's work is a phenomenal example of how this kind of cooperation can go well; ISACs can be a great way for defenders to share information while limiting their legal exposure.

Defenders & law enforcement have more options than just "set up MFA" and "arrest the bad guys, but, like, they kinda have to walk into our office for us to pull that off." Strikeback operations & coordination across jurisdictions and countries can be effective. How we incur costs on threat actors is then seen by threat actors, which can be used as a disincentive structure. "I don't want to do [insert attack type & target here] because the last time someone did that, [insert law enforcement agency here] went and [doxxed their admins | broke all of their servers | prioritized them as a target and actually arrested them | made it impossible for them to leave the country & enjoy all of that money they stole]." Law enforcement has a lot of control over everything in the brackets there.

Economic productivity is largely a measure of efficiency—how much economic output a company, industry, or country can produce given a constrained set of inputs. Well, productivity in the ransomware sector, which I'll use here as a proxy for financially-motivated cybercrime writ large, is fantastic. Revenue in the ransomware industry grew 500% between 2019 to 2024 for a compound annual growth rate of almost 40%. Compare this to some other ways you might be able to invest your money like the S&P 500 which performed 17% over that same period. Don't even get me started on the S&P 500 without the past ten months of AI-hype-based growth concentrated into a few specific companies. It matters how quickly they've grown because this represents how quickly they move, how lucrative it is for existing and potential attackers to pursue new attacks, and how well-funded they can be for their next attacks.

If your retirement advisor offered you a part ownership in a ransomware gang, without telling you what you were investing in, you'd be a fool not to put your money there based on their fundamentals.

03. Why should I care?

"Cool trends, nerd. Get a hobby. What's in it for me?" – the average (presumed) reader.

Let's use an illustrative example, ex post facto, so that I can't completely blow smoke. I'm going to use Google Trends as my authoritative source on "what the industry cares about" for two reasons: first, it's not proprietary data, so I can't get in trouble for sharing it; second, it supports my argument, so I'm not going to work any harder than I have to. We'll look back at a couple points in time in the last five years, focused in the secure access arena, and see how the above observations about attacker incentives can help us predict the next chapter in the security story.

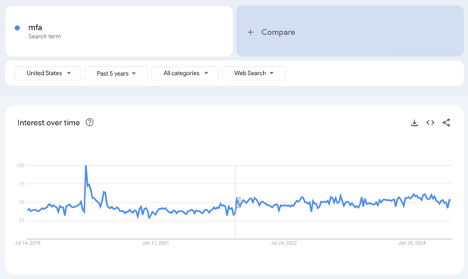

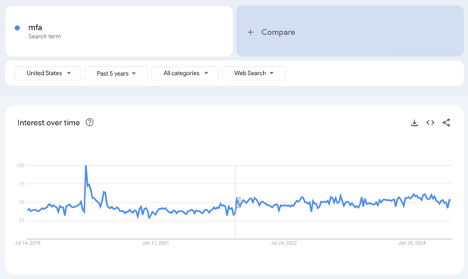

Take my hand. Walk with me back in time to easier days, back to 2019. Take a deep breath. Isn't that nice? Nothing has gone wrong. You don't know who Joe Exotic is. You do know that MFA protects you better than single-factor authentication, so you use it in your environment. You're in good company here—a lot of people do this.

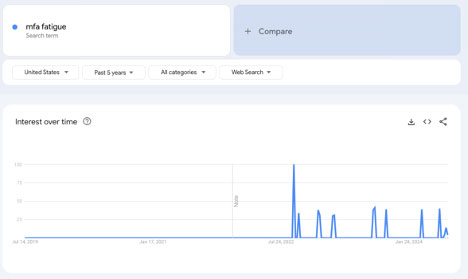

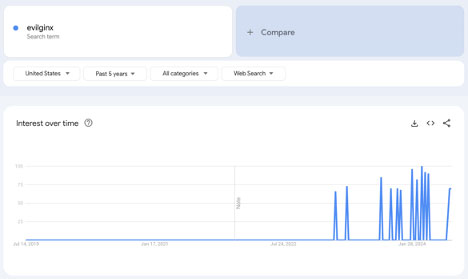

(all of these Google Trends shots run from mid-July 2019 to mid-July 2024).

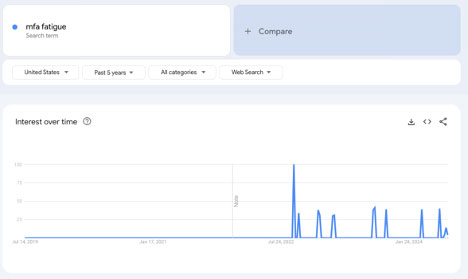

So, what do we expect from attackers, who are rational actors, pursuing the highest payoff potential at the lowest cost? They're going to start chatting with each other about how well it works to just…send MFA requests to end users. Enter MFA Fatigue attacks.

In the summer of 2022, these attacks drastically increased in frequency, as well as in visibility—defenders started talking about them a lot more. So, what did builders do in response to demands from defenders to protect against this? Okta, Microsoft, and Duo developed some version of code-matching MFA in their existing push-based applications for authentication. These policies rapidly gained adoption in organizations that were affected by timing attacks and fatigue attacks in second-factor authentication after a primary credential compromise.

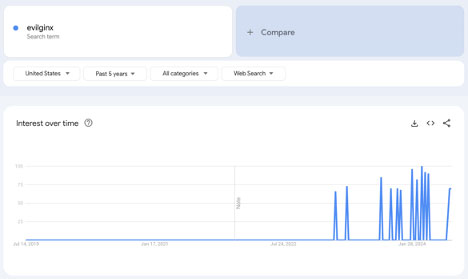

Again, I ask, what do we expect from attackers, who are rational actors, pursuing the highest payoff potential at the lowest cost? They're going to find the cheapest, highest-fidelity way to bypass MFA—now including number-matching solutions. For most, this meant AiTM approaches, either running their own kits or purchasing phishing-as-a-service deals with newly popular Initial Access Brokers. This started in earnest in 2022 and hasn't let up since.

WebAuthn-based authenticators have since grown in adoption, and hopefully will continue to with the advent of Passkeys.

What's happening now? We're seeing indicators that generative AI is improving the scalability and success rate of large phishing campaigns, and that attackers are adapting to disguise their infrastructure in response to common detection techniques.

Now, if you were an attacker, a rational actor, pursuing the highest payoff potential at the lowest cost, what would you do? I've got my bets and may as well go on the record here: I think that infostealers and social engineering will be increasingly used to gather session tokens & other access credentials from corporate devices, leading to session replay attacks; I also believe that the common use of (often, not corporate-managed) mobile devices for access to resources (especially for messaging, email, and calendar purposes, which end up holding all types of juicy data) will become increasingly popular attack vectors. Personally owned smartphones often lack the same levels of controls as primary workstations. There, I said it, I'm on the record. Email me in two years and prove me wrong!

04. Some things will mature

There are limits to this thesis. I don't intend to come across as Chicken Little; I am actually quite optimistic about the future of the industry and our collective ability to improve the security of our world. However, to do that requires a pragmatic view of the players in the arena, such that we invest our time, effort, and resources in the right ways.

Best practices will continue to develop. What I don't expect is that we end up in a "solved" industry—one in which nearly every problem can be addressed by a best practice, one in which best practices haven't changed in decades. Security certainly has its fair share of practices; I recommend a few on a daily basis. But other areas of security are not nearly that developed yet. Even in my little neck of the cybersecurity woods, best practices have had to evolve over the past few years.

I also believe that we will continue to develop a better ability to quantify and predict risk. We may not get to the point of the automotive industry, which is highly regulated, well-informed, and where best practices are standardized and widely adopted, but we can take steps to get there. Perhaps we can at least get to the point of the home insurance industry, which has clear lines delineating who is responsible for what costs, between homeowners, insurers, reinsurers, and the federal government (your home either is, or is not, in a flood zone - there's no confusion there). We can make intelligent decisions over what risks we subsidize, and who ultimately holds the bag between the insured, the insurers, the reinsurers, and the government. The cyber industry is not there yet.

And finally: on that note of change. I don't think that security is the only industry in which change will happen. That's a bit self-congratulatory from a guy who likes working in, well, security. But I do believe that there's a unique element to change in the security industry given the fact that it solves problems caused by active, incentivized, intelligent opponents. It's one big game theory arena including adversaries, which is a marked change to the landscape for most companies (who, if we're to believe this Harvard Professor guy, will include competition, new entrants, suppliers, customers, and substitutes…sometimes expanded to also include the regulatory landscape). Security has all of those elements, plus adversaries, and that matters. I think.

05. What this means for builders

You can pay attention to many things that inform your prioritization and roadmap. Just don't confuse fads or compliance with security value. Know that these have different values, and that you should educate yourself on them from different sources.

Realize that you can absolutely identify attacker trends in time to develop real, impactful solutions to active threats before attackers have moved on. If you market yourself as a security product, but have no quantitative research function into your product data and qualitative review with customers who have experienced incidents, you are losing out on a critical source of not just security value but also asymmetric business advantage.

You are able to learn from a number of sources, including those that aren't directly related to your area of expertise. Any technical report that is able to provide insight into attacker attribution or motivation can help you understand how an attacker might pivot their TTPs—and therefore their relevance to your slice of the security pie—in the future as new protections take hold. This creates fertile hunting grounds for strong opinions lightly held.

You are well-positioned to advise your customers on new threats. This is a moral responsibility, not an opportunity to help yourself to their wallet. You focus on your one area of expertise; your customers have to manage your one thing among many, plus a bunch of screaming end-users who just got locked out of something and batted away six warning messages in order to open up The_Tortured_Poets_Department.mp3.exe. This means that you ought to know enough to be able to help inform them on your domain.

You are well-positioned to help inform policy. This can serve to your commercial advantage, sure. It can also improve the resiliency of industries as a whole.

You are well-positioned to help other builders. Be diligent and purposeful in your reasoning to not share information. Grow comfortable with sharing blogs, writing reports, and opening up your secrets. Cybersecurity is largely a reputation-based industry; this is not giving away the secret sauce, this is establishing yourself in the eyes of customers as the type of chef who can make really good sauce.

06. What this means for practitioners

You are responsible for learning more than is really reasonably feasible. You don't need me to tell you that, but it's worth explicitly addressing this. Be purposeful in your information diet: ISACs are your friend; LinkedIn influencers may not be. There are strongly diminishing returns to quantity here - you're well served to improve the quality of the information you consume, not necessarily the quantity.

Be diligent and purposeful in your reasoning to not share information. OPSEC has its value; overclassification has costs, too. Understand them and keep them in mind. Just like Builders, benefit the rest of the world, where you're able to, by giving updates about what trends you've seen, and how you've been able to detect and respond and mitigate them.

Compliance isn't security. I'm not the first to write about this. Don't confuse the two.

You're tied to security, in large part, by the accountability you hold for it. Use that same dynamic to your advantage; try to drive accountability and align incentives within your organization that are in your favor.

07. TL;DR

"I ain't reading all of that. I'm happy for you tho. Or sorry that happened" - the first three coworkers I asked to proofread this time.

Security is described as an immature industry because of the truth that compliance (insurance), best practice, and regulation lags far behind today's threats. This is largely for two reasons: first, like all Big Tech™ industries, the technology is changing regularly. However, the second reason is more unique to security: we've got attackers in our industry in addition to the interested parties that are present in all industries (competitors, customers, suppliers, regulators, new entrants, substitutes). This means that change in security will continue to happen at a rapid rate, and there will never be an opportunity for compliance, best practice, or regulation to "catch up" and mature the industry.

The storm is up, and all is on the hazard.

With that said, there are patterns we can derive from attackers and, from these, we can play a bit of game theory to make predictions further out than the end of our collective nose. By looking at threat actors as rational actors, we are able to recognize changes in threat models, our own organizations, and in technology adoption that will drive their behavior: financially motivated threat actors are attracted to high payouts; to high probabilities of success; and to minimize their probability of legal or other material consequences. This has led them to organize and specialize, which relies largely on trust, brokered by newer trends like cryptocurrencies.

Builders and defenders play a role in this incentive system, and their share of agency in this ecosystem can drive better outcomes for all of us. This article has largely been a call to action for those who have an influence in the industry: recognize the incentive structures that exist, and what negative externalities can be wrought from them, and fight them where you can. It's in all of our best interests to share everything we can.

"If you have knowledge, let others light their candles in it."